![]()

One of the main influences in Malta’s history has been religion, so it’s not surprising that you can scarcely turn a corner anywhere in the country without finding a church. The most important contributing events were the expansion of the Turkish empire during the Renaissance, and the rise of the Knights of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem.

The Knights were a military medical order founded in 1048, who became prominent during the Crusades. They arrived in Malta by sea in 1530, after the Turks expelled them from Rhodes. It was their heroic efforts and sacrifices in holding the Turks at bay for years, and finally repulsing them for good in 1565, that ensured the continued dominance of Christianity in Europe. They soon became the island’s protectors and remained the country’s most important political and cultural influence for nearly 300 years. They added greatly to Malta and Gozo’s existing church legacy, so that today there are some 350 churches, ranging from chunky fortresses to exquisite cathedrals. In this one tiny country you can see the evolution of church architecture, function and decoration from the Middle Ages through the Renaissance to the modern era.

![]()

In Valletta

Three of the many churches merit special attention. The most historically significant is the co-cathedral of St. John, built by the Knights in the 1570s. It doesn’t look like much on the outside, but I was just overwhelmed by its baroque and yet tasteful atmosphere from floor to ceiling inside. Sir Walter Scott once called it the most beautiful interior he had ever seen.

It’s not uncommon in Latin countries to find heroes entombed beneath church floors, and that usually makes for a pretty uneven walking surface. Not here: the smooth polished marble floor of the nave covers the graves of some 400 Knights, whose colourful armorial bearings are themselves works of art. The cathedral staff wouldn’t let me set up my tripod until they had personally checked the soft rubber tips, to make sure they wouldn’t scratch the floor. The ceiling is enriched with biblical scenes of great beauty and intricacy. Nowhere do you see the gaudy excesses of gold leaf that we find in some other countries.

![]()

History and culture are everywhere in this cathedral. The great Italian painter Caravaggio painted some of his finest works while serving there. The cathedral museum contains his priceless 1608 masterpiece The Beheading of St. John the Baptist, while one of the nine chapels on either side of the nave contains his well-known painting of St. Jerome. Since Knights were the cream of wealthy Catholic aristocracy, they vied with each other to present the most impressive gifts to the Order to commemorate promotions or special events. Gold and silver treasures and works of art came to abound. Even though Napoleon’s troops looted the churches and carried off most of the Order’s silverware on their way to Egypt in 1798, the sacred items on display today are both priceless and tasteful. (Napoleon got his "just desserts": he never got to benefit from his plunder, because Nelson sank the ship containing it at the Battle of the Nile).

Also in Valletta we find the baroque – and to my mind somewhat garish – church of "Saint Paul’s Shipwreck". The good saint, you see, was shipwrecked along with St. Luke in Malta in 60 AD. Legend has it that after being bitten by a viper on the site of the present church he banished all snakes from the island. (Could that tale stem from some Maltese desire not to be outdone by St. Patrick?) In any event, he then proceeded to convert the Roman governor to Christianity – much to Emperor Nero’s displeasure and Paul’s eventual martyrdom. There is an artifact in the church, donated by a pope, which is reputed to be the very block on which he was beheaded.

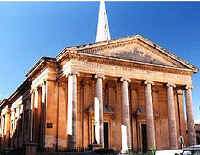

Disgusted with the actions of Napoleon’s troops, the Maltese revolted and invited the British to become their protectors. Thus Malta was a British colony from 1800 to 1964, when it became an independent republic within the Commonwealth. It is not surprising, then, to find that the Anglican church has also had a certain influence, as shown by Saint Paul’s Anglican cathedral in Valletta. It was built with her own funds by Queen Victoria’s aunt, Queen Adelaide.

Like St. John’s, it has a military heritage, but of a different sort. It contains more modern artifacts, including the tattered RAF flag which flew at the airfield throughout the horrendous Battle of Malta, and the flag of the sole surviving tanker of an American convoy sent to re-supply the desperate island. For decades the Anglican cathedral’s spire was a landmark for seafarers, and in an interesting bit of good-natured one-upmanship the dome of the nearby Carmelite church was made a few feet higher when it was rebuilt after the war.

![]()

Elsewhere

Speaking of domes, they are prominent throughout the two islands. Saint Mary’s, the parish church of the small town of Mosta, has the world’s third largest dome (after St. Peter’s and St. Paul’s). It was built in the mid-1800s around the existing church, which was later demolished.

During WWII the population of the town used to huddle in the church during air raids. In April 1942, in an act of supreme contempt, Axis pilots dropped three huge bombs directly onto the packed church. Two bounced off but the third one smashed right through the dome and landed in the middle of the terrified congregation, but did not explode. It was subsequently disarmed, and now occupies a place of honour in a small room near the altar under a copper bas-relief of the Virgin miraculously shielding the church. It’s one of the major tourist attractions of the island.

![]()

In mediaeval times churches had to be more than places of worship. They were sanctuaries, and often fortresses. Such was the case of the cathedral in Victoria, the capital of Gozo, which is still surrounded by cannon. It bore the brunt of Turkish assaults in the 1550s, and was largely destroyed by an earthquake in 1693. When it was rebuilt it featured a unique and unforgettable work of trompe l’oeil art. Its Italian architect couldn’t imagine a church without a dome, but the local population couldn’t afford such a grand venture. Determined to leave his trademark nevertheless, the architect cleverly painted a perfectly proportioned "dome" on the flat ceiling. It’s only when you walk under it, and it doesn’t change, that you realize it isn’t real.

Among other interesting churches are the co-cathedral in Mdina (also rebuilt after the 1693 quake), and a brand new parish church in Gozo, whose dome is just slightly higher than that of St. Mary’s in Mosta. Talk about rivalry!

This has only been a brief look at Malta’s religious heritage, which in turn is only one of the interesting aspects of this fascinating country.