On the Road to Nowhere: 12 Hours in the West Bank

Israel & the Palestinian Territories

|

|

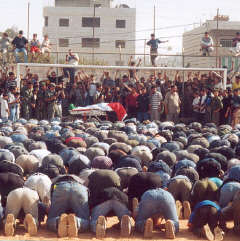

The crowd simultaneously knelt down to pray |

The machine gun fire got louder and louder as the traffic snaked through the center of Hebron. Youths ran past our taxi, their faces covered, waving giant Islamic Jihad flags. We got out of the taxi outside what looked like a ramshackle football stadium. Crowds were milling about outside and on the pitch hundreds were running around chanting. Most had gathered at the goal at the opposite end of the pitch. It was only when they simultaneously knelt down to pray did the situation become apparent. Under the goalposts lay a body lying on a hospital bed, draped in the flags of Islamic Jihad and Palestine. Then the praying stopped and the chanting got louder and louder. It was then we noticed the foreign press, mainly camera crews, most wearing some form of body armour. We were slightly unprepared in comparison with our shorts and funcams.

The crowd, now about 3000 strong, left the football stadium and began to march down the main street. Automatic gunfire raked the air as the chanting became louder and more passionate. ‘God is Great’ was the only chant I could make out, that and some certainly unflattering remarks about Israeli Prime Minister Sharon. The atmosphere was electric, although far from intimidating. We were stopped once or twice and asked for ID, but once we showed our Irish passports there were apologies all round. The main emotion seemed to be exuberance.

|

|

The martyr’s son (with the rifle) |

These funerals for ‘martyrs’ are the one occasion where the ordinary Palestinian can vent his spleen at Israel and the rest of the world. For a people so subjugated, this is their escape, their release valve from the pressures of the occupation. They can chant, wave their national flag and assert their nationality in a relatively safe way. These funerals are not so much about mourning but about celebrating. Celebrating their right to resist, to fight the occupation, a nod to Israel – “Look, you may be destroying us but we are not destroyed yet”.

While there are obviously the hardcore militants in the crowd, most seemed just there for the ride. And let’s face it, if you were unemployed, your day consisting of endless cups of coffee and cigarettes, a procession of masked gunmen firing Uzi’s into the air and burning effigies of international statesmen would surely arouse some interest. The procession wound it’s way around Hebron’s narrow streets for about an hour before reaching the cemetery. The victim’s father was led through the crowd to the site of the grave while the victim’s son stood on an overlooking ledge firing a massive AK-47 into the air. The chanting died down a bit now as most began to pray for the deceased. At this point we figured the action was over so we made our way back down towards the center of town.

|

|

Crossing the No Man’s Land of an Israeli road to get to Hebron proper |

Hebron in 2001 is a lot different to Hebron 2000. For a start the old market is deserted, strewn with rubble, twisted bits of metal and broken glass. The intifada has taken a heavy toll on the locals, virtually all of whom are now unemployed. Walking through the once bustling markets is now like walking through no man’s land. There are two Jewish settlements in Hebron, both in the center of town. We approached soldiers guarding the Kiryat Arba settlement who told us to turn back. We ignored their instructions and kept

walking. The Jewish and Arab property was virtually indistinguishable from each other, it is so intertwined.

Rounding a corner into yet another narrow alleyway, we heard shouts and saw four Palestinians running away from us. Eventually they stopped and started shouting Arabic and then Hebrew at us. I began to get a bit worried, not knowing who they were or what they wanted. Eventually one stepped forward and shouted a greeting. We returned it and he began to smile and walk towards us. It turned out he thought we were Jewish settlers and had began to run away, fearing the worst. Eventually we were invited into his home, a narrow four storey house right in the centre of the town. From his roof we could see IDF soldiers on rooftops watching us. They were guarding the Jewish settlements less then 500 yards away. Our host, Mohammed, began to get nervous and ushered us inside. The bullet holes that covered his rooftop door explained why.

Over a meal of rice and chicken, Mohammed explained his situation to us. He was 44, a builder by profession who had been unemployed for 14 months. He was literally confined to the town, as were his friends, their days now consisted of drinking endless cups of coffee and chainsmoking. Mohammed and his friends were unsurprisingly bitter about their situation. He believed the Western media were unfailingly pro-Israeli (just as almost all Israelis saw the press as pro-Palestinian) and laid the blame for the violence squarely at Israel’s door. Despite their situation they were genuinely friendly, offering us a roof for the night if we couldn’t get a taxi back to Jerusalem. We left the centre of Hebron and got a taxi to take us back to a road block, where we crossed no man’s land and got another taxi towards Jerusalem. Unfortunately things didn’t go to plan.

After about twenty minutes we came up to an Israeli checkpoint. The soldiers told us we couldn’t continue as a settler had been shot minutes before and the road was closed while the IDF searched the area. Just to illustrate the point, the bullet ridden car of the dead Israeli was driven past us. The soldier told us to go down a side road which would take us to Bethlehem. It was now dark and our taxi driver seemed to be getting more and more agitated. We followed the soldier’s instructions and drove up a pitch black dirt path, the battered taxi barely able to maneouvre the rubble strewn road. We turned a blind corner, and BANG, straight into the back of an IDF tank.

Suddenly we were in the shit.

A light was directed at us, as were the machine guns on the back of the tank. The soldiers began to scream in Hebrew as to our left and right barrels of guns were pointed at us by camouflaged soldiers hiding in the bushes. Our driver was shaking as he turned off his lights. Bad move. This seemed to annoy the soldiers as they began shouting even more wildly and seemed to be extremely nervous. A nervous eighteen year old with an automatic weapon doesn’t make for a good time and at this stage I though it was curtains. It wasn’t unknown for suicide bombers to drive up to army patrols and blow themselves up. How could the soldiers tell who we were? I thought about getting out and shouting that we were merely lost tourists, but instead resigned myself to the inevitable and crouched down by the driver, listening for the crack of automatic fire as I waited to die.

We sat in that position for what seemed like an age before the driver, still with his lights out, began to slowly reverse. All the while machine guns were still being pointed at us. Eventually we got back to the main road where our driver got out and began praying. I needed a cigarette. And a pint. And a clean pair of trousers.

We drove up to the same roadblock and began shouting at the soldier who had given us the directions. Gun or no gun I was very close to ramming his radio up his arse. After he had calmed us down he explained we were stuck at this roadblock for the foreseeable future until the road was reopened. We got chatting to the soldiers, who in fairness were only doing their job. They were all about 18 or 19 and shared a mixture of boredom and edginess that all soldiers on checkpoints seem to exhibit. I was surprised at our Palestinian taxi driver’s friendliness to the soldiers and soon everyone was laughing and joking with one of the soldiers trying to explain to the Palestinian why the road block was like a condom.

I was surprised by how relaxed the soldiers became and soon things descended into farce. Myself and one of the soldiers played “keepy up” with a tennis ball. Another soldier was on the phone to his girlfriend, while the taxi driver and my friend, Tristan, were half asleep, spreadeagled on one of the breeze blocks that made up the road block. This all came to a halt when what looked like a Shin Bet operative came by in a jeep and began shouting and pointing at the general pathetic state of the road block.

The road had now reopened and we made our excuses and left, heading through an eerily quiet Bethlehem before finally making it to the outskirts of Jerusalem. We headed straight for a pub, the Putin Bar, a bizarre place in the Russian compound of Jerusalem where scantily clad females were dancing on tables to Soviet pop music. The contrast was as immediate as it was obvious. Here, not 30 minutes drive from that roadblock, were people getting pissed and dancing to crap music. The contrast between the life of the average Israeli and the average Palestinian was also fairly evident. While the residents of Hebron were confined to their homes at nightfall, fearful of attacks by both the settlers and the IDF, the residents of Jerusalem were free to do what they pleased. While the Palestinians might not be the most brutalised people in the world, they are certainly one of the most humiliated.

While it is true that Islamic extremism leads many young men to become suicide bombers, it is also true to say that the Israelis have created far more. The general feeling of helplessness, with Arafat, with Israel, with the West, leads many to think the only way they can make an impression is to blow themselves up, preferably along with a few Israelis. The major feeling I got in the West Bank was a curious mixture of acceptance and defiance. Acceptance that no one was going to help them, not Arafat, not the Arabs, not the West. But there was also a defiance. A defiance that no matter what the Israelis have or will do to them, they will never lie down and take it.

|

|

Jewish settlement |

The journeys through the West Bank also led me to the conclusion that the core of the problem (as 99% of the world accepts) is the occupation. End the occupation and the chances for creating future suicide bombers will decrease dramatically. Violence inevitably occurs when the two groups of people interact with each other. Take away the interaction and the violence will also lessen. South Lebanon is a good example of this. The hawks in Israel said that withdrawal from Lebanon would only cause Israel to come under heavier attack from it’s enemies. They failed to grasp that the reason for the violence was the occupation of Lebanon, not some deep seated hatred of the Jews by the Lebanese. And now the border is quiet and the violence has all but disappeared. The same result can occur should the occupation of the territories end.

However, given the attitude on the Israeli side (most of whom have no intention of ever relinquishing control of the territories) that day is a long way off. Having said that, travellers should not be put off by the violence in the West Bank. The people there are incredibly welcoming and the picture of the situation becomes much clearer when seen without the filter of the mass media. There will, sadly, always be violence in the Middle East, so now is as good a time to go as any. Base yourself in Jerusalem and travel widely through the territories. Visit the refugee camps, visit the Jewish settlements and make up your own mind.