While spending a year in South America I found it interesting to learn about the differing national icons of the various countries we visited. It began to become apparent to me that you can tell a lot about a country by the people they idolize. Here are some examples.

Peru – Alberto Fujimori

I first read about Alberto Fujimori, former leader of Peru, in my guidebook before arriving in Peru. I learned that he was a gentleman of Japanese ancestry who prematurely ended his rapidly deteriorating presidency in 2000 by faxing a letter of resignation from Japan, where he had sought and received political asylum. Subsequently wanted in Peru on charges of financial corruption, election fraud, and human rights abuses, he had remained in Japan, far away from Peru, since then. With these facts fresh in my memory, I found it most unexpected to repeatedly see “Fujimori 2006” spray painted on rocks, buildings, and billboards throughout the high Andes upland communities of Peru. Could Alberto Fujimori, a wanted exile, possibly be running for reelection in the upcoming Peruvian presidential election? Further research confirmed that Mr. Fujimori was indeed hoping to be reelected as president of Peru. He had publicly announced his intent to run for President in October 2005, the same month that I arrived in Peru.

I first read about Alberto Fujimori, former leader of Peru, in my guidebook before arriving in Peru. I learned that he was a gentleman of Japanese ancestry who prematurely ended his rapidly deteriorating presidency in 2000 by faxing a letter of resignation from Japan, where he had sought and received political asylum. Subsequently wanted in Peru on charges of financial corruption, election fraud, and human rights abuses, he had remained in Japan, far away from Peru, since then. With these facts fresh in my memory, I found it most unexpected to repeatedly see “Fujimori 2006” spray painted on rocks, buildings, and billboards throughout the high Andes upland communities of Peru. Could Alberto Fujimori, a wanted exile, possibly be running for reelection in the upcoming Peruvian presidential election? Further research confirmed that Mr. Fujimori was indeed hoping to be reelected as president of Peru. He had publicly announced his intent to run for President in October 2005, the same month that I arrived in Peru.

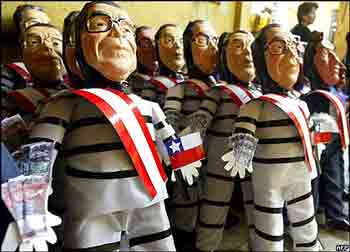

Fujimori traveled unannounced to Chile in November 2005, apparently to launch his reelection campaign from Peru’s southern neighbor. Perhaps he thought he would be safe in Chile since the current governments were squabbling over offshore fishing rights at that time. Having an enemy of the current Peruvian administration, such as Fujimori had become, safely harbored in Chile would likely be an embarrassing slap in the face of current Peruvian officials. Chile, however, did not react as Fujimori had anticipated. Based upon an Interpol international arrest warrant for murder, kidnapping, and crimes against humanity, as well as a formal request from the Peruvian government, Chilean authorities arrested Fujimori uncontested in his hotel room. So Fujimori’s aspirations of reelection faded as he was incarcerated in a Chilean corrections officers’ academy. As of February 2007, he was conditionally free based upon a bail payment of $2,830. Terms of his bail specified that he was free to move about Chile but not free to leave the country. He had still not been handed over to Peruvian authorities fifteen months after his arrest in Chile.

As we traveled through Peru during his failed reelection campaign, the demographic divisions of Fujimori support became obvious. Support was very evident in the poorer, Andean highlands while not so evident, if at all, in the wealthier cities of the lowlands, such as Lima. Support was especially concentrated in those areas that were formerly under control of the Sendero Luminoso (Shining Path), an insurgent Maoist terrorist group that effectively controlled up to sixty percent of Peru in the early 1990s. I spent two weeks learning Spanish in Huancayo, a city formerly under the control of the Sendero Luminoso. In fact, one of Fujimori’s alleged crimes against humanity occurred in Huancayo. Sixty-seven university students from Huancayo accused as terrorists were rounded up and subsequently never seen again. Speaking with one of our Spanish instructors who had grown up in Cusco, I learned how her childhood memories were tainted by the recollection of living in fear of the Sendero Luminoso. Kidnappings and murder were commonplace until Fujimori’s “death squads” deprived the terrorists of their control of fear in these regions of Peru. I asked the Spanish instructor of her impressions of Fujimori and her response was, “All politicians are crooked, but at least Fujimori did some good things for us.”

Instead of ignoring the poorer people of Peru, as had been the norm of past presidents, Fujimori took action and brought them schools, roads, and, most importantly, freedom from terrorism. To the people of these regions, it was the neglect of prior administrations that had allowed them to fall under the control of the Sendero Luminoso and it took a man as strong and determined as Alberto Fujimori to liberate them. They were not so concerned if he broke any rules or conducted any human rights violations while ending the reign of those who had persecuted them for so many years. That was something only the wealthy opposition politicians in Lima were worried about.

It was becoming clearer to me how a wanted man could indeed be running for president in a country such as Peru. His support was a telltale sign of the large geographic and economic division between classes in Peru. A minority of the population was wealthy and urban and concentrated in cities such as Lima and Arequipa while the remaining majority of the people were poor and rural. He had proven his support for the often neglected poor people of Peru in his previous administrations and they were grateful for that support and, given the opportunity, willing to vote him back into office.

In April of 2009, after a lengthy trial, Fujimori was sentenced to 25 years in jail for human rights abuses. Thus, the long and convoluted public political career of this icon for many appeared to be at its end. Or is it? Alberto Fujimori is planning to appeal the verdict.

Chile – Arturo Prat

Arturo Prat is Chile’s greatest hero. He was a naval officer who achieved martyrdom in the Naval Battle of Iquique, part of the War of the Pacific between Chile, Peru, and Bolivia. Throughout Chile, Arturo Prat is immortalized. Most major towns and cities have an Arturo Prat Plaza, Arturo Prat Boulevard, or an Arturo Prat statue or memorial. His portrait appears on the Chilean 10,000 peso bill. One of Chile’s Antarctic research facilities is named in his honor. It is hard to travel far in Chile without wondering, “Who was Arturo Prat?”

I was to learn about Arturo Prat and his heroism in a maritime museum in Punta Arenas, a city with a long naval history along the Straits of Magellan. An Arturo Prat memorial in the museum contained a detailed account of the heroism he exhibited in the Battle of Iquique, for which he is passionately remembered by all Chileans. A naval commander, his primary mission was to defend the coastal town of Iquique from enemy Peruvian naval forces. The invading Peruvian navy possessed boats (armored ships) and firepower highly superior to the Chilean navy (unarmored ships). Shortly after the Battle of Iquique began, Arturo Prat realized that, barring surrender, his soldiers’ hours were numbered. He gave a stirring speech aboard his ship to motivate his men in spite of the overwhelming odds they faced. When the Peruvian iron-hulled warship rammed the Chilean wooden ship, Arturo Prat jumped aboard the enemy ship, charged the enemy, and was promptly killed by enemy bullets and forever immortalized. His remaining men followed his lead and did likewise, boarding and storming the enemy ship each time it rammed their ship, only to be easily killed by the enemy. The Peruvian naval forces easily won the Battle of Iquique.

Were these passionate men? Yes. Were they brave men? Yes. Were they patriotic men? Of course. Arturo Prat exhibited all those qualities, as did the men he led. Did Arturo Prat make the right choice by bravely, patriotically, and passionately leading his men to certain death against the Peruvian forces? I do not know. I think the answer to that question may be more questionable. Whatever the answer may be, after my time spent in Chile, I can’t help but wonder how glorifying an individual who exhibited such blind and passionate bravery impacts the psyche of the people of one’s country.

Chileans indeed seemed very passionate and patriotic, but somewhat rashly so. Overall, Chileans did not appear to be too inquisitive. They tended to make decisions based upon emotions rather than rational thought. Much like the soldiers who followed Arturo Prat into martyrdom―and the portion of the populace not tortured or killed during Pinochet’s brutal reign―Chileans did not appear to question what they were told. It appeared to me that a majority of Chileans’ behaviors and thoughts were determined by others’ perceived expectations rather than by what they themselves believed in. It is unfortunate that the lack of the development of independent thinking appears to be a lingering impact of the brutal sixteen-year Pinochet reign over the Chilean consciousness.

This impression was bolstered whenever I ventured into a Chilean bookstore. They just were not the types of bookstores I was accustomed to. You will not necessarily find any works of literature in a Chilean bookstore. Rather, you are likely to find trashy periodicals and tabloids. Conversations with foreign students attending university in Santiago, as well as with a few candid Chileans confirmed my suspicion that Chileans tend not to read too much. Unfortunately, a relic of the Pinochet regime’s effort to suppress the flow of independent press, information, and education―a ten percent book tax―is still in effect today. Books in Chile are disproportionately expensive. It is not uncommon for motivated Chileans to travel to Argentina to purchase their books. Until this archaic tax is repealed, it will remain that much more difficult for Chileans to expand their knowledge with the wealth of information available in most other country’s bookstores.

A most ironic episode that occurred in the seaside Chilean village of Isla Negra really imprinted this impression of Chileans upon me. Isla Negra is the location of one of Pablo Neruda’s homes. Pablo Neruda was a world-renowned Chilean poet and political activist. He is widely considered one of the greatest and most influential poets of the twentieth century, winning the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1971. All of his three former homes, including the one in Isla Negra, are now museums and popular tourist attractions. I had an opportunity to operate a hostel in Isla Negra for a week. Each day I walked down to the Pablo Neruda museum, headed to its seaside café, got a coffee, and enjoyed reading as I listened to the crashing ocean swells directly below the café. Is there a better way to enjoy your time at a museum for a literary figure such as Pablo Neruda than to read at the very location where he wrote many of his best works? I didn’t think so. As I was to learn towards the end of my week in Isla Negra, however, the employees at the museum and café apparently thought otherwise. My behavior was considered rather odd, in fact. I ran across some of the off-duty workers one night. They were a bit rude and cracking a few jokes at my expense. They were actually making fun of me for reading at the café! They sarcastically asked what I was studying in my “big” book. What are you studying? Why are you studying? Are you learning a lot? Are you smart? They could not comprehend why somebody would go to a café by the sea and “study” a book. I was completely flabbergasted. I was being made fun of for reading at a museum dedicated to one of―if not the most―noted literary figures of Chile by the actual employees of the museum! How ironic is that? To put it in perspective, imagine going to the home of Ernest Hemingway in Key West, Florida, and enjoying a coffee and a good read for a half hour or so. Can you imagine running into the employees later that day only to have them point and make fun of you for actually reading at the home of Ernest Hemingway? I find it hard to believe that that could happen. Unfortunately, this incident has proved to be the most lingering in my overall impression of Chileans.

Argentina – Diego Maradona

Anybody who knows the slightest bit about international football (or soccer as we like to call it in the United States) already knows about Diego Maradona. He played for Argentina in four World Cup tournaments. He led the Argentinean team to victory in the 1986 World Cup and was named the tournament’s best player. Diego’s most legendary game came in the 1986 quarterfinals against England, during which he scored both Argentinean goals in a two-to-nothing victory. The second goal was an astonishing play in which he picked up the ball in his own half and ran more than half the length of the field while dribbling past five English players and ultimately the goalkeeper. This goal was voted the Goal of the Century and Diego was voted best footballer of the twentieth century in an Internet fan poll. Diego was not only one of the best footballers, he was also one of the most controversial. He was suspended for fifteen months from club matches in 1991 after failing a drug test for cocaine in Italy, and then again during the 1994 World Cup, when he tested positive for the illegal performance-enhancing drug ephedrine. In addition to scoring the best goal of the century, he also scored the most controversial goal of the century. It also occurred in the 1986 World Cup quarterfinal match against England and has become simply known as “The Hand of God.” Replay videos and photographs clearly showed Diego illegally scored the goal by striking the ball with his hand. Despite the protests of England about the illegitimacy of the goal, the officials allowed it to count. At the post-game press conference, Diego exacerbated the controversy further by claiming the goal was scored “un poco con la cabeza de Maradona y otro poco con la mano de Dios” (a little with the head of Maradona and a little with the hand of God), thus coining one of the most famous quotes in sports history. Ultimately, in 2005, Diego admitted on his television variety talk show that he hit the ball with his hand purposely, and that he immediately knew the goal was illegal. He recalled thinking right after the goal that I was waiting for my teammates to embrace me, and no one came… I told them, “Come hug me, or the referee isn’t going to allow it.” Diego also acknowledged it in his autobiography. Now I feel I am able to say what I couldn’t then. At the time I called it “the hand of God.” What hand of God? It was the hand of Diego! And it felt a little bit like pick pocketing the English.

What I found during my time spent in Argentina is that Diego is just one of the more well-known practitioners of viveza criolla. We learned about the concept of viveza criolla in a book entitled Bad Times in Buenos Aires which is a firsthand account of an English woman who lived in Buenos Aires. Although viveza criolla does not exactly translate into English, it can be loosely defined as an artful act of cheating. For many, the Hand of God is the premier example of the possible glory to be gained by effectively practicing viveza criolla. Yes, Diego did punch a ball into the goal with his hand in a World Cup game, but he got away with it―the goal counted―and that is just perfect for the people of Argentina.

The more I read up on the concept of viveza criolla, the more it explained much of the behavior of Argentineans that I found irritating. Waiting in lines was optional. Unless you speak up to announce otherwise, you will be cut in line. Stores and businesses often gave me the incorrect amount of change or overcharged me for my purchases. Being a mere tourist with no pull to exert on government bureaucrats, I found it nearly impossible to deal with an institution such as the postal service. I read an account that claimed in school Argentineans learn to get by however the best they can, most often utilizing viveza criolla tactics, as opposed to learning the nuts and bolts of thinking and problem solving. Another account described viveza criolla as a means to gain maximum benefit to the minimum opportunity, without scrimping means to use, nor the consequences or damages for others. Ultimately, I learned that some have surmised that viveza criolla is such a prevalent aspect of Argentinean culture that it can be considered to be one of the main contributors to Argentina’s chaotic political and economic history. Here is an example of one such account:

Corruption pervades all levels of society and all institutions in various forms: privileges, favoritism, cronyism, bribery, and so on. It is endemic, deeply embedded in all structures of public and social life. . . . in this context, personal effort and merit are often pushed aside by opportunism, which slowly undermines the foundations of a healthy work culture. The Argentinean expression “viveza criolla” encapsulates a way of life characterized by making the least possible effort, ignoring the law and seeking individual advantage over any other interest. Throughout history, politicians have acted as accomplices to this tendency by accepting gifts in return for political favors. In addition, there is a widespread assumption that it is the State’s responsibility to solve problems that could be better dealt with by determined and committed citizens. (Mele, Domenec, Debeljuh, Patricia, and Arruda, M. Cecilia, Corporate Ethical Policies in Large Corporations in Argentina, Brazil and Spain, Working Paper 509 University of Navarra Business School, June 2003)

I found it amazing to learn that the Argentinean currency has been replaced a total of five times since 1969 because of large-scale collapses of the Argentinean economy. Is it possible that this concept of viveza criolla is partially―or perhaps greatly―responsible for this alarming fact? Maybe Diego Maradona knows.

Photo courtesy of AFP