“OK, gringos. Time for your initiation into Inca culture.”

Our Peruvian guide Wayo is at the door of our van, just returned from a nearby tienda (store) with an innocuous pink bag in his hand. He hands over the bag and invites me to take a look inside. I open it to reveal the small green leaves within, each about the size of my thumb.

“With these leaves,” he states, only somewhat tongue-in-cheek, “you will have the energy of the Incas. You will ride all the way to the ends of the empire, like the chasquis who ran these trails hundreds of years ago.” He is as giddy as a schoolboy. I suspect he has already sampled the bag’s contents.

In my hand is a healthy portion of coca leaf, enough to land me seven hard years in a Canadian penitentiary. I am holding a plant with an illustrious and controversial history. Unlike its infamous derivatives crack and cocaine, coca has therapeutic properties and is held sacred by the inhabitants of the Andes. For thousands of years, they have used the coca leaf to improve digestion, relieve headaches and mitigate the negative effects of altitude. In spite of this it is feared and outlawed by most governments of the Western world.

I take a wad of leaves, give a short prayer of thanks as is Inca custom, and wrap the leaves around a small piece of llipta – the hardened ash of the quinoa plant. The whole package takes up an uncomfortable and intrusive residence in my cheek.

The juice slowly seeps into my mouth; it is is pungent yet pleasing. My tongue is buzzing and my cheek soon goes numb, but I feel a surge of energy. My 3 riding companions, observers until now, tentatively follow suit.

“Welcome to Peru!” gushes Wayo enthusiastically when we are done.

“Now we are ready to ride.”

—

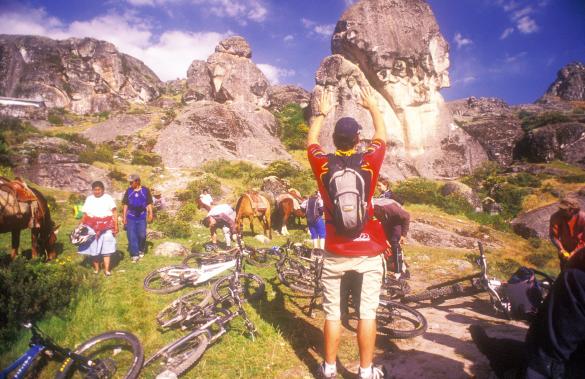

We are six mountain bikers high in the Andes of Peru, intent on reaching Machu Picchu via the system of trails laid out by the Incas centuries ago.

Despite living in the Canadian Rockies for a decade, I’m not prepared for the sheer scale of the Andes. These are mountains, in the most imposing sense of the word. The Andes are the longest mountain range in the world, and Peru contains more than a thousand mountains over 5,000 m above sea level.

Canada has five.

We are at 3,200 m in Andahuaylas province – the pradera de los celajes, prairie of coloured clouds. Today we will get our first taste of the main Inca trail – the Camino Real, or Royal Road.

Among the many roads and trails constructed in pre-columbian South America, the Inca road system of Peru was the most extensive. Traversing the Andes and reaching heights of over 5,000 m, the trails connected the regions of the Inca Empire, covering approximately 22,500 km and providing access to over three million km2 of territory. The Camino Real was the most important of these ‘roads’, with a length of 5,200 km (3,230 mi).

The trail isn’t really a ‘trail’ in the mountain biking sense of the word – the sport is still fairly new and undeveloped here. It’s more like an intricate Brobdingnanian web of meandering and intersecting foot- and animal paths. The 1,500 m descent is as long and challenging as anything I’ve ridden. Loose rock and exposure force me to concentrate solely on the few metres of trail in front of me. It’s exhilarating – I have to remind myself to stop and take in the awe-inspiring scenery. Halfway down, I briefly lose concentration and fly over the handlebars into the arms of a cactus. It takes Wayo 20 painful minutes to get all of the needles out of my ear.

We pass through villages where dusty Quechua-speaking campesinos (peasants) smile curiously and wave. Farmers wearing the vibrant clothing typical of the Andes harvest potatoes from their fields and sing in the midday sun. By late afternoon I am lost in the rhythms of these awesome mountains.

Racing against the fading sun, we pull into the remote town of Huancarama in total darkness. The rock-hard mattresses of the El Gordito (Little Fat Man) hotel are as welcoming as waterbeds. In my exhausted, satiated state I fall asleep within minutes, grinning and fully clothed.

—

Two days and 170 km of Inca trail later, I awake under a spectacular stone wall with a splitting headache. I look up in a laboured effort to get my bearings. Last night… Cusco? Mmm-hmm…. Discos? Yes. Cervezas? Many.

Have I passed out in one of Cusco’s narrow stone alleyways?

I survey the scene once more. No, I am under two inches of warm blankets in a cozy hotel room. A hotel room with an extraordinary 10-foot-high Inca wall.

Welcome to Cusco, the former capital of the Inca Empire.

There’s something tragic about this bustling colonial city. Under Francisco Pizarro the Spanish massacred most of the city’s Inca inhabitants and constructed grand cathedrals and mansions on top of the original architecture. Much of this architecture would have remained hidden forever had a massive earthquake in 1950 not unearthed much of the original stonework. The Inca were renowned masons whose work still defies explanation. Many of the city’s alleys are lined with detailed and ornate brickwork; stone jaguars and serpents watch menacingly as tourists pass by oblivious to their stares.

Despite the crush of tourists it is easy to befriend the locals of Cusco; I spend my afternoon drinking tea with a craft vendor selling his wares in a quiet back alley. That evening I give in to one of Cusco’s surprisingly professional $10 massages and dine on cuy al horno. The roasted guinea pig is a Peruvian delicacy and is delicious despite being somewhat tough and stringy.

I eschew a second round of discos and retire to my room under my personal Inca wall. I fall asleep while the throb of electronic music fills Cusco’s main square.

The next day begins with a massive breakfast of fruit salad, eggs, homemade pan, and generous doses of mate de coca, or coca tea. The tea arrives without asking. It is ritual in Peru, as normal as coffee is in North America. After two cups of this heady brew I am buzzing once again. It relieves my altitude-induced headache and fills me with energy for the day’s upcoming adventures.

Soon we are on our bikes following the Urubamba River through the Sacred Valley, once one of the most resource-rich areas of the Inca Empire. Riding through this valley today, it is not hard to see why; the earth here is a deep crimson red and the crops are bountiful, unlike the hardscrabble terraced agriculture we’ve seen elsewhere in Peru.

The riding is majestic; around us 20,000-foot peaks tower above the small villages dotting the pastoral landscape. Russo, our Quechua-speaking guide, teaches us a few phrases that endear us to the locals. He is the Peruvian national cross-country mountain bike champion and thus somewhat of a hero in these parts.

The trail drops sharply into a narrow canyon. The exposure is scary but electrifying. We stop at an Inca mine where salt is still mined today the same way it was thousands of years ago. From there the trail descends once again to the Urubamba River.

To protect the wealth of this valley the Inca built a series of fortresses, most of which survive to this day. One of these former fortresses is Ollantaytambo, now a quaint village of 2,000 that we enter via cobblestone road. Ollantaytambo is surrounded by ruins and is one of the main jumping-off points for the journey to Machu Picchu and host to hordes of adventure-seeking tourists.

Tomorrow we go to The Lost City.

—

The 7:30 a.m. train ride through the Sacred Valley is both sublime and sordid. Lush green mountains line both sides of the Urubamba River while hordes of trekkers, guides and porters line the tracks. UNESCO has threatened to withdraw Machu Picchu’s World Heritage Site status unless Peru gets a handle on the throngs of people crowding the Inca trail and leaving masses of litter and pollution in their wake.

At Aguas Calientes, a small town at the base of Machu Picchu, we crowd onto the bus in a heightened state of anticipation. The energy is palpable among the travelers on board this spiritual express.

“Machu Picchu,” I yell as we ascend. “We’re going to Machu Picchu!” With iconic images of the storied citadel etched into my memory, I can hardly believe that I’ll actually be there within minutes.

We arrive at the gates of the Lost City amid a crush of tourists. Leaving our guide behind, we quickly lose ourselves in Machu Picchu’s serpentine mazes. Despite the tourists and the cost of getting here, it is worth every cent. My fellow travelers and I look at each other knowingly and remain silent as we explore, aware of the futility of words in a place such as this.

Theories abound as to the ancient city’s purpose. What is certain is that it was abandoned for over 400 years when American Hiram Bingham ‘discovered’ it in 1911. I look out over Machu Picchu and imagine how Bingham must have felt after hacking his way through the jungle to discover this otherworldly place.

We climb the nearby peak of Huayna Picchu in the pouring rain – typical weather for this area. Upon reaching the summit, I find a place away from the tourists on an outcropping of rock. Sitting silently in the mist and rain, I gaze out over the surreal landscape. It is unlike anything I have ever seen before.

—

For the Incas, the mountains were gods – apus who could kill by a variety of means: volcanic eruptions, avalanches, and climactic catastrophes.

On our final day in Peru, these violent deities are angry with me: I’m sick and weak, beaten down by the altitude, late nights in Cusco, and long days of riding. It seems the apus are angry with my compatriots as well, so a consensus forms that we should drive to the top of our last day’s ride. We file into the van for the last time as our driver Joselo straps down the bikes. This, Wayo assures us, will be the icing on the cake, our Homerean epic to cap off our Inca journey.

We climb. And climb. And climb… on and on and on. It feels as if we are ascending to the very roof of the world. We pass through rustic villages, past pre-Inca ruins and herds of alpacas. Farmers offer bottles of chicha to our open windows. The air is getting thin.

As we arrive at the start of the trail, I check my altimeter: 13,945 feet, over 4,270 m. It is going to be a long ride, Wayo informs us. The scenery is barren, grey, and forbidding. A few alpacas are the only other living beings in sight. I chew a little harder on my coca and llipta wad and swallow a big mouthful of juice.

I’m nervous.

The trail is epic all right; rocks the size of grapefruits litter the trail and alpacas scurry out of the way as we push our bodies and bikes to their limits. One of our riders narrowly escapes a fall into the river when his front wheel slips on a technical descent. As we descend, we pass through narrow canyons, along Inca irrigation canals, through hamlets virtually untouched by the modern world. It is unlike any ride I have ever done, neatly combining stunning scenery, challenging riding and vibrant culture. It feels as if the Incas foresaw the advent of the mountain bike by a few centuries.

We arrive in the town of Calca soaking wet, covered in dirt and thoroughly spent. Women in traditional garb walk by and stare. Schoolchildren in bright white uniforms giggle and point at our muddy bikes and strange outfits.

The sun has returned; for now the apus are not angry. They have welcomed us into their valleys, their canyons, and their mountains. I smile and reflect on what was, without a doubt, the best mountain bike ride of my life.

I’m changing into dry clothes in the comfort of our van when a hand slaps me on the back. I turn to see Wayo, our perpetually grinning guide. I smile back at my new amigo. It has been an eventful and exciting 10 days since we first met at the airport in Andahuaylas.

“Congratulations, my gringo friend,” Wayo says as he offers an outstretched hand. “Welcome to Peru.”