The journey from the empty quarter to Madain Saleh, Petra’s “sister city”, passes through Qassim, an area renowned for its desert delicacy, dates. The road also goes through some of the most conservative areas of Saudi Arabia. I wouldn’t equate conservative with militancy, but not long ago a small group of French tourists were killed here. There are conflicting stories. I was originally under the impression that they were ambushed while hiking in. I later heard that the murders happened on-site. One certainty is that the locals are historical rivals to the house of Saud and could only benefit, politically, by offing the random infidel; the Kingdom has a complicated and somewhat tenuous peace. Thus, I was a little on edge and wondering what lied ahead.

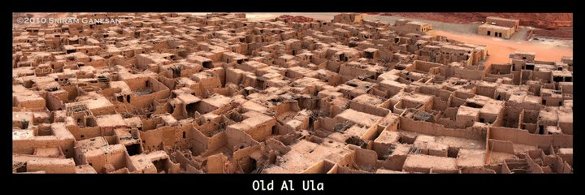

I arrived in al-Ula, late and tired and began the search for a suitable hotel. This was rewarding in itself because I happened upon a fairly large and crumbling, well-lit mud-brick settlement downtown. It was reminiscent of Siwa, Egypt, minus the surreal ambiance and breathtaking baths, and so not really like Siwa at all, but it did provide a glimpse into the Arabia of just 50 or so years ago. Saudi is undergoing an amazing transformation, one that is likely only just beginning, fueled by oil.

The next morning, having forgotten to make the necessary permit arrangements (a week) in advance, as required by the current bureaucracy, I began the palm-greasing ritual. An employee at the hotel, I’ve forgotten his name, faxed Riyadh with my details and within an hour I had some paperwork that, inshallah, would get me through the gate. He made no promises. I thanked him, cast my traveler’s-snobbishness aside, and set out looking for a camera. As I drove down the road a man in traditional Saudi garb, thobe and red checkered head scarf, pulls up alongside me in a white SUV and gestures for me to pull over. Thoughts of a duct tape gag, rope burns, and a gurgling demise, ran through my mind. I was reluctant. But, he looked vaguely familiar. I pulled over, got out, and we met half way. He informed me that Madain Saleh was in the other direction. I thanked him and said I needed to find a camera first. It was true, but, more importantly, provided a convenient excuse to distance myself from this intruder. He then said, “I police man”. We shook hands and departed.

I ended up following him on the only road into town. He stuck with me, showing me to several different stores. The last one, staffed exclusively by Afghanis, tried to sell me three different cameras, but none of them worked, so I gave up. By this point I had realized that the “policeman”, Yousef, was in fact escorting me. I was getting good vibes, but couldn’t shake the idea that he could also just be one smooth, evil-intentioned guide. I told him it was time to go to Madain Saleh and left. He stayed in front of me before deciding to pull over for gas, at which point I seized the opportunity to ditch him, and gestured that I was going ahead.

The brief peace of mind that followed after waving good-bye to Yousef was quickly replaced by thoughts of the unlucky Frenchmen mentioned before. You know, “What should I do if…?” It seemed like the pragmatic thing to do.

Suddenly, Yousef was flying past me and urging me off the road. Why was he so persistent, I wondered, my suspicion renewed. I pulled alongside him and he again corrected me, saying, in effect (he, supposedly, didn’t speak English), that I had missed the turn. Red flags were going up. I had been very careful to follow the signs. Torn between the feeling that I was on the right path, and not wanting to offend someone who appeared to be helping me, perhaps showing me a shortcut, I indulged in the latter, with adventure on my mind and a consciousness of my recent oath-to-self: to get over that lingering fear—death. I surveyed the roads anyway, the small settlements, the general topography. I watched Yousef through his rear window, as if, for example, seeing him on the phone would provide any indication of an impending okie-dokie. I felt safe. And a couple of miles away, I was soon jumping out of the car and working my way past the guards, courtesy of Yousef, who then showed me to the first tomb before adamantly refusing a generous tip and excusing himself.

After a few hours, and a few follow-ups from Yousef, I was ready to leave.

He wasn’t to be found at the gate (probably praying). I checked out with the guard, who felt compelled to make three phone calls on two different phones. The content, bear in mind I don’t speak Arabic yet, seemed to be that the “Americi” was now headed to either Medina or Riyadh. As I had told him, I wasn’t sure myself. Riyadh was my final destination, and via Medina was a tempting route, though I was uncertain as to whether or not non-Muslims were allowed in. Yousef said it was no problem. Others have said there is one path for the Muslims, and another for the disbelievers. Could this, I wondered, be a metaphor for the “straight path”?

Between the concierge, Yousef, the guards at al-Hijr (Madain Saleh), and the history of every kingdom I’ve read about, it seemed reasonable to suspect that someone in Riyadh was keeping tabs on me. But why use two different phones? Was he a “double-agent”? Would I soon be diverted off the road? My paranoia, or superstition, if you will, remained.

The drive to Medina was remarkable. I’ve never seen such a desert-scape. I’ve never before come so close to smashing into a giant camel at over a hundred miles an hour either. There were what appeared to be ancient lava flows but that were now massive rock fields looking so formidable that I don’t even think Bear Grylls would enter. There were the mountains, and a desert fauna that resembled areas of New Mexico, Utah, and at times, Southern Idaho. And then, of course, there was the history. I was on the cusp of the Muslims’ second-most holy site. The place where Islam was born. Where the Prophet (sallallahu aleihi wasallam) established the first mosque and umma (Muslim community). Where he arranged to retake Makkah from the “idolaters” of the day. Where he died and where he is buried.

If there was a checkpoint, I didn’t see it. I entered the holy city and immediately a palpable tranquility and easiness, unlike any other city I’ve ever been in, took hold of me. The location, unsurprisingly, was gorgeous. And the Prophet’s Mosque, well, easily the most impressive one that I’ve set foot in. I found it as the azan was calling the faithful for asr, or the afternoon prayer. And, as if it was written, I found a parking place less than two blocks from the main courtyard and joined the others in walking, humbly, to the sound of silence, in the middle of a city of millions. Every act, in Islam, is one of worship or profanity. It’s believed that every step, towards the mosque, for the believer with the right intention, yields benefit from above; like a prayer in itself. Men embraced hands, allowing their sins to drip, like water, off their hands—as recorded in the sunna. There were people from all over the world representing their homelands in dress. And then there was the huge marble courtyard with the massive, elaborate, retractable umbrellas to shade it. Beautiful minarets piercing the sky. An interior modeled on the mosque in Grenada. Majestic gold and blue patterns on retractable vaulted domes. Silent air-conditioning, by virtue of having the cold air pumped through the desert from a site(s) several kilometers away. And tens of thousands of gentle worshipers.

Photos by Sriram Ganesan and may not be used without permission