I’m what you might call a traveling introvert. What I mean by this is when I travel I tend to settle for what’s visible from my roving bubble of photo opportunities and observations. Sure I’ve gone to various exotic backwaters but even so, I still only look out from behind my isolated sphere of traveling solitude – a tourist’s curse. Over the years I’ve attributed this to a variety of things: language barriers, victimizations and other unavoidable culture conflicts but in the end I’ve remained content to appreciate my journeys via camera lenses and the food I put in my mouth. It’s not the best way to travel, but it is one way.

This all changed last June over the final days of a two-week run through Croatia. My wife Caitlin and I arrived in Dubrovnik after meandering down from the north: Istria, Plitvice, Split, delicious locales seen from beyond a gulf of countertops and car windows. Dubrovnik would come to be different – we had a contact there, a person who would end up as our doorway to the entire population.

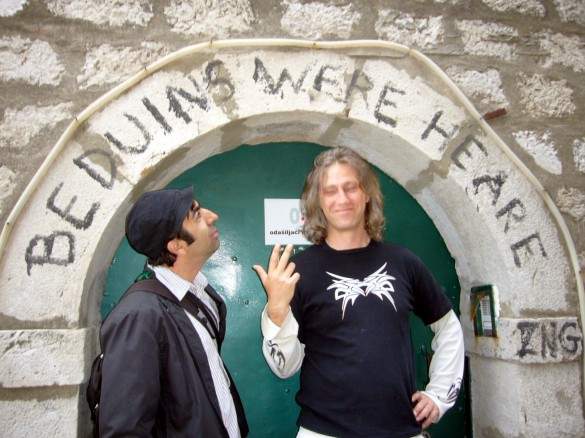

Michael, an old work colleague and Dubrovnik resident, met us at the Pile Gate at the west end of the Old Town just after sunset. He greeted us like we were old cousins. Shortly after and without so much as a passing thought, he brought us to a gathering on a friend of his’ patio, a brick enclave hunkered under a hillside of heavy green foliage. The friend’s name was Damir, a Dubrovnik lifer but also, we found out, a combat veteran of the Bosnian War and someone who could trace his lineage back to an 800-year-old Dalmatian king. He had a detailed and baroquely decorated family tree hanging in his living room. Damir was an extroverted surfer type, more a Balkan Jeff Spicoli than a vessel of royal blood, but whatever, Damir was a great guy with a very deliberate temperament.

We relaxed into the night and one-by-one engaged the six of the fourteen local Dubrovcani we’d come to meet over the next six days. Not two hours in and we already felt unquestionably “in the fold”. By far more that we expected to come of that night. More Croatian was spoken than English on the patio but the energy was undoubtedly one of acceptance, as if we’d been celebrating with them every night of our lives.

We stayed there late into the night and I couldn’t help but be fascinated by how easy it all seemed, the migration from alienated tourist to fashionable scenester. How could it have taken so long to get to this point? I leaned back into the chaise and let the bourbon and the night air embrace my veins. I grabbed Caitlin’s hand and squeezed it tight.

It wasn’t until the last day of our stay however that Dubrovnik was immortalized as one of those places you wish every traveling stop could be—an instrument of cultural sensitivity and a lesson that no matter where you are in the world, people might just as easily be your brother, your cousin or your best friend.

Our agenda that day contained two things: hitting the beach and attending a barbecue, which in Croatia meant divine waters and as much meat as you can cram in your gut. It also meant time spent with people who would make us feel as if Dubrovnik desired us more earnestly than our hometown could ever do.

The beach was an intimate semi-circular cove slivered between two hundred-foot tall rocky crags. We met Michael’s kids there, a cute cowering daughter of twelve and a ten-year-old son, quite possibly the most fearless boy I’d ever met. He jumped off several of the more precarious overhangs on those cliffs, out through space and into the succulent blue water below, emerging from underneath with a gasp but otherwise almost completely unaffected.

And the five of us settled in, letting wave upon wave of Adriatic air slip by as breezes, submersing ourselves in the water and the personalities of other Croatian sun worshippers who kept approaching and joking around in a language that was, to us, incoherent as their friendliness was sincere.

Later at the barbecue we cooked Ćevapčići (pronounced chevapchichi), the seasoned, salty, high-caloric sausages that made up a fair percentage of the average local’s diet. A handful of people we’d met on Damir’s patio and bumped into repeatedly over the course of the week arrived with armfuls of beer and the late afternoon sun sank slowly taking with it the one millionth color of the day.

The evening was filled with conversation drifting in and out of our native tongue. People laughed and smiled and reveled in beer, joints and all the flavors of the still-grilling chevap, and it was then that we felt the closest to Croatia, as if from somewhere deep within its scented tussocks was a wild beating heart matching mine in intensity. I could feel my sphere of isolation moving slowly but convincingly toward oblivion.

Later, as Dubrovnik drifted to a close, a genuine sense of melancholy passed not only over us but also Michael and Damir and those new friends with whom we got a chance to bid farewell. They all seemed quite sad to see us go.

After the Balkans, I couldn’t help but wonder if this was the way it always could’ve been on the road, new friendships bridging the continental abyss, taking shape by way of a lone chance architect, one that so casually peeled away the shells of unfamiliarity to reveal the tender flesh of the unguarded, people quick to take on foreign friends like so many handfuls of grass from the hillsides. I wondered at that point if my traveled-hardened sphere of protection might never have even existed, so freed did I feel from it at last. I wondered also if it might never even return.

Nico is an introspective traveler now in his 40th year, the last 23 of them dedicated to seeing as much of the world as possible. He writes and maintains the travel blog at AirTreks.com and one purely personal, highlighting his love of art, music and photography called 10 Times One.