Editor’s note: We have been publishing transformational travel stories on BootsnAll for a while now, and up until today, they have all been first person accounts of how travel has changed or transformed that particular writer. Today’s story is a little different in that the writer, William Blomstedt, writes about a man he met during his travels – a man in his eighties who is still out exploring the world – and how that meeting and his subsequent travels with his new friend impacted his experience.

We only meant to spend a few minutes using the internet in the hotel lobby, but before I knew it I was running the four flights of stairs to our room for the third time, this trip to get the iPhone’s USB cable. When I returned to the lobby, Bill was posing for a photo with a kid under each arm. He had a jacket on backwards displaying the words “Israeli Youth Kickboxing Team” across his chest, and the two kids stood next to him with frozen smiles. Seated in nearby chairs were a twenty-something Japanese backpacker and a 14-year old Israeli kickboxer with spiked-up hair, having a get-to-know-you conversation. Bill had recruited the first for internet technical assistance and the second to write a message in Hebrew to one of his friends in Tel Aviv. My technical fumbling had kicked me out of the driver’s seat, and I had been demoted to a mere gofer.

Once they figured out the iPhone and took the picture several times over, Bill began telling a story about a dinner he ate with “the second in command’ of the Entebbe raid. After a diplomatic mission in Israel years ago, it was Bill’s request to eat dinner with this esteemed man, and his wish was granted. I didn’t know about the Entebbee raid, and when I interrupted with this fact the entire Israeli youth kickboxing team, a dozen kids and two adult chaperones, began an animated history lesson. But before they could get too in depth, the Japanese backpacker announced that he had fixed the internet. Bill thanked him, gave him one of his cards, and told him if he was ever in Georgia to stop by. The Japanese boy smiled and said that if he ever needed help with the internet to let him know.

“I will, I will,” Bill said, and gave me a wink.

By then it was time for the Israeli group to take the bus across Belgrade to the World Youth Kickboxing Championships. The message in Hebrew was written, the picture was downloaded and attached, and as the team left the lobby, we promised to come to the arena and cheer them on. Bill sat down in his chair to rattle off a few emails and check his stocks. I sat down in the chair next to him, nearly exhausted. It was 11 AM on my first day with Bill.

Meeting Bill

The previous morning I was on a train from Sofia, Bulgaria to Belgrade, Serbia, one of the legs of my journey from Turkey to Slovenia, where I would be studying for the year. I had boarded the train at the last minute, and it seemed like I would be standing in the aisle for the entire trip, when a compartment door opened and a woman signaled me towards an empty seat. I wrestled my bags in the overhead holders and settled in, thankful to have a seat among these chatty Bulgarian women.

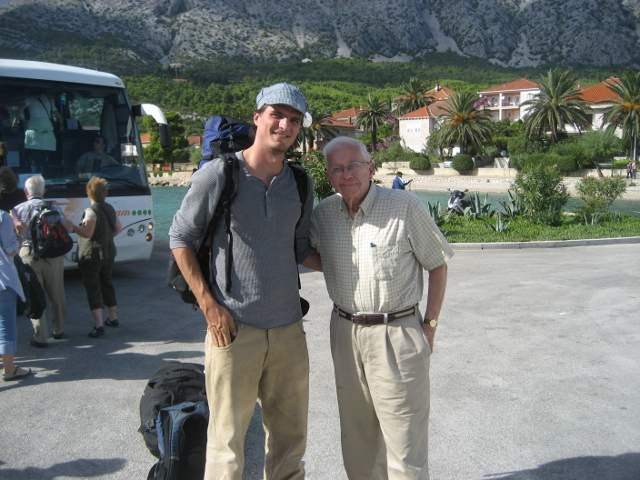

Minutes later I noticed an old man standing in the corridor. He was wearing pleated khakis belted up above his hips, brown sneaker-shoes and a plaid short-sleeved shirt. He wore glasses, his white hair was combed back from his bald top, and next to him stood a rectangular rolling suitcase under a folded jacket bag. There was something that made him distinctly different from anyone I had recently seen in Bulgaria and Turkey – he looked like my grandfather, but he seemed to be traveling alone, in a second class train and without a seat for the eight hour trip. The mystery deepened when he pulled out a mobile phone and began speaking English in a distinct, jarring accent that I knew, but couldn’t immediately place.

After only a few minutes one of the Bulgarian ladies in my compartment left and I poked my head out the door to invite the old man to the seat.

[social]

“Where you from?” he asked and the accent clicked: a southern drawl. The heaviest I had heard since living in Texas. I didn’t recognize it because it wasn’t even on my radar of accents to be listening for in Bulgaria.

“America,” I replied.

“Well I know you’re from America, what do you think I was born yesterday? I’m an old man, I’ve been around. What part of America?”

“I grew up in Massachusetts.”

“Ahh, a Yankee.” He smiled and shook his head. “I’m a redneck; my name’s Bill.”

Bill was born and raised in a small town in Georgia, and the day I met him he was 82 years young. He had just come from Varna, a city on the Black Sea, where he had spent a week merely because he had never been there before. In Varna he had eaten the best meal of his life and returned to the same restaurant for the same meal three nights in a row. After a ten hour train ride to Sofia the previous day, he had stayed at a cheap hostel next to the train station and ate cookies for dinner because the hostel was in a rough part of town with no restaurants nearby. Now he was on his way to Berlin and had a month to get there. Interesting guy was my first impression; I can’t say I had ever met an 82-year-old who traveled by himself, stayed in cheap hostels, and rode second class on a foreign train. It wasn’t long until he turned the questions on me.

“What are you doing?” He asked.

“I’m on my way to Ljubljana.”

“Is it money or for a girl?”

“Um, neither.”

“Good. Most all boys your age are going somewhere either because of a girl or money. So, why Ljubljana?”

“I’m going to study for the year on a Fulbright Scholarship.”

“Fulbright, huh. You know, I knew Bill Fulbright.”

“Really?”

J. William Fulbright, the U.S. Senator from Arkansas? Who began the Fulbright Program in 1946? Who was the longest serving chairman in the history of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee? Who Bill Clinton cited as a mentor? This redneck from Georgia sitting across from me on a train in Bulgaria happened to know “Bill” Fulbright?

Bill’s stories

It turned out that this Bill worked as a lawyer on Capitol Hill for most of his career. With nearly any political name that came up in conversation, his eyes would twinkle and a story would soon follow; like the time he had been a guest at a dinner in the White House, or how he had met John McCain’s grandfather, as well as Preston Bush. And he was particularly proud of never once saying hello in passing to Nixon, which apparently irked the former President.

Bill didn’t only talk about politics; he had stories about everything and nearly everywhere. He met the king of Norway. He slept in Tito’s summer house in Bled, Slovenia, in Tito’s former bed. He ran with the bulls in Pamplona on his 80th birthday. His political career had taken him all over the world, and he had been to 108 countries in his lifetime. At some point amidst the conversation, stories, and laughter on the eight hour train ride, I found myself agreeing to divert from my planned route and to travel with Bill to Sarajevo, Bosnia, for him to see his 109th country.

With his track record, that sort of recommendation carried serious weight for a curious traveler like myself, and my excitement began to build.

Though I am usually all for an interesting adventure, the decision to go to Bosnia was not automatic. My problem lay in the baggage – I wasn’t packed to be mobile. I had a year’s worth of stuff, both winter and summer clothes spread out over three giant bags, and any sort of transfer between train and hostel required a herculean effort. I had originally planned to bee-line to Ljubljana to set up my life before any thought of travel.

But I didn’t have a set schedule, and when Bill said that after Sarajevo we could travel to the Croatian island of Hvar, his favorite place in the world, all of the nagging baggage-thoughts disappeared. With his track record, that sort of recommendation carried serious weight for a curious traveler like myself, and my excitement began to build. When the train reached Belgrade, we found a hostel across the street, then a nearby restaurant for dinner, and our journey together began.

The journey begins

Despite our differences in age, politics, and just about everything, Bill and I got along really well. This was because: 1) he liked talking, and I liked listening, 2) we both shared an interest in the people of the world, and 3) we traveled under a similar philosophy, which I embodied in my decision to join him on the trip to Sarajevo – a flexible, open-minded method of travel, where one jumps at interesting opportunities and is willing to go out of the way for a personal connection.

When traveling, Bill never makes plans. He sets a destination but is open to diversions, and being a highly charming fellow, these seem to come in torrents. After striking up a conversation with a perfect stranger (“Do-ya have five minutes?” he’ll ask, before beginning a barely tangential story), one out of every few will invite him for a drink, to their house for dinner, or to come visit them in, say, Bergen, Norway. Bill never accepts the first offer: “You have to ask me three times,” he advises the potential host. When they repeat the offer he’ll say, “That’s twice,” and wait for the third. But as sure as he is asked for a third time, Bill will one day show up on that doorstep in Bergen, Norway, and will boomerang the offer for his host to come to visit him in Georgia.

We traveled under a similar philosophy – a flexible, open-minded method of travel, where one jumps at interesting opportunities and is willing to go out of the way for a personal connection.

Bill is also an advocate of budget travel, and this can be seen as a reflection of his life work. His career goal in Washington was to cut reckless spending, fight inflation, and erase the national debt. “Our country needs to stop thinking it can just print up more and more money,” he’ll say when the topic arises. As a token, Bill carries with him a small card with an old German stamp attached to it. This stamp was from the frightening hyperinflation incident of the 1920s, where it cost a couple million Deutschmarks to send a single letter. At one point he gave a copy of this card with the actual stamp to every member of the US Congress, as a stark reminder about what could happen if our nation’s spending habits did not change.

As a part of his budget traveling, Bill often stays in hostels. His eyes were opened in the 1990s when he first stepped into a hostel in Norway, “I saw young kids from countries all around the world, Germans, Americans, English, Japanese, all eating, drinking and laughing together, getting to know each others’ cultures and see each other as other people. I thought to myself – if there is going to be a way to world peace, this is it.” He even opened his own hostel in Atlanta, Georgia, sometimes recruiting the kids to work on his ranch in the countryside for a more in-depth travel experience.

Other than the cheap accommodation, Bill enjoys the social aspect of hostels. At one point he admitted that his wife and kids were a little tired of hearing his stories, but in the hostel social scene new sets of ears await him every night, and for those of us with any form of travel addiction, he can be seen as a kind of aging rock star. With a host of nations seated around the hostel table, Bill provides a sort of conversational lubrication with his international knowledge and encyclopedia of stories, often pulling in strangers by amiably mocking their homelands. When they try to turn the tables on him, Bill is prepared because one of his favorite topics is other people’s impressions of America. In the debate that ensues, Bill offers an older, more conservative point of view, one that is not often seen on a hostel couch, and it is quite refreshing.

In the debate that ensues, Bill offers an older, more conservative point of view, one that is not often seen on a hostel couch, and it is quite refreshing.

But hostel traveling is not exactly comfortable, and at 82-years-old Bill told me that he was reaching the end of his career. This trip from Bulgaria to Berlin was his “last trip” to Europe, and I was to accompany him to Hvar for the final time. Later on, he admitted that he had said this before, and this was actually his sixth “last trip” to Europe; he kept getting pulled back every summer. “But this is the last one, I’m getting old, and I’m serious this time,” he said before asking me, a few hours later, if I wanted to travel to Israel with him next spring.

The next day we went to watch the World Kickboxing Championships, and after arriving back at the hostel, Bill announced that it was my job to find a good place for dinner that night. He was going to get a bowl of soup and a massage. Massages were another part of Bill’s travel plan.

Some years ago Bill had been suffering from depression which stemmed from the strain of heavy family responsibilities; one of his daughters had suffered a serious brain injury and one of his granddaughters had albinism. Both required a significant amount of time, thought, and care, and the strain made him seek help from a therapist. But a moment came when he decided that instead of paying a therapist, he would rather use the money for travel and massages. With the combination of getting away and the physical massage, as well as his highly-social method of traveling, Bill created a variation of therapy that made him much happier than laying on a couch and talking about his problems.

The pros and cons of “flexible” travel

The next day, after getting more technical support from our Japanese backpacker friend, we hiked across the street to find a bus to Sarajevo. While we were waiting for departure, Bill struck up a conversation with a Serbian man named Damien, who had moved to Pennsylvania during the Bosnian War but was back to visit his parents. As we got on the bus, their conversation continued, and we ended up sitting across from each other and talking for nearly the entire ride.

Bill has the incredible knack of finding the most interesting people in the room, as if they have a light glowing around them that only he can see. This is something I lack; I am often introverted when I travel, preferring to stew in my own thoughts and watch the passing scenery unless someone actively engages me. This incident showed me my fault, for Damien could have been a history professor, and he gave us an in-depth lecture on the breakup of Yugoslavia, as well as the differences between ex-Yugo countries. Bill and I grilled him with questions, and the information we received felt more true and alive than reading it from the pages of any guidebook. All along the way, Damien gave us the disclaimer that his was a Serbian perspective, and he encouraged us to talk with a Bosnian while in Sarajevo to hear the other side. A few days later we found a Bosnian who gave us a drastically different story, and hearing the two side-by-side was a blunt lesson on what a confusing, scary place this had been in the 1990s.

Bill has the incredible knack of finding the most interesting people in the room, as if they have a light glowing around them that only he can see.

We arrived in East Sarajevo on a night of spitting rain. Neither Bill nor I realized there was a difference between East and West Sarajevo, and the part of town where the bus left us did not seem too welcoming. Landing at night in an unfamiliar city without a place to stay is not a particularly pleasant experience. These are the times when the flexible travel philosophy loses its romantic flavor and survival becomes the goal. Though I could see Bill was pushing for a place to stay with Damien, no offers were made, and we had to find a place to stay on our own. Our best option was to take a cab to the other side of the city and look for a cheap hotel.

The cab driver first brought us to a hotel which was full and then left us at a giant Holiday Inn. The Holiday Inn was overly expensive, so we decided to try our luck at another place they recommended about a mile away. Without our cab we went by foot onto the deserted, wet streets of Sarajevo, as the dark windows of the massive American Embassy watched this strange pair pass by. Bill led the way with his rolling suitcase and jacket bag, while I sweated and cursed behind him under about 100 pounds of luggage. It didn’t take long before it really began to rain.

“Here’s the deal,” Bill said to me when we found ourselves hiding under an unlit railroad bridge. “I’ll stay here with the luggage. You go find a place.”

I looked at our bleak surroundings and a wave of emotion smacked me; one of those moments in life when I take a step back and ask myself “How in the hell did I get here?” Shards of memories pieced together; lying on my kitchen floor fifteen years ago and listening to a news report of massacres, sieges, and bombings in this very city. Could I have ever thought I would be here on a dark, rainy night, homeless and huddled under a bridge still decorated with bullet holes, and leaving all my stuff to be guarded by a geriatric redneck?

At each passing moment this travel philosophy was losing its appeal. Wouldn’t it be much easier to spend a little more money, plan everything out, and just enjoy oneself in museums, meals, and sightseeing?

Without dwelling on it, I took off at a fast clip towards a nearby lit road. At each passing moment this travel philosophy was losing its appeal. Wouldn’t it be much easier to spend a little more money, plan everything out, and just enjoy oneself in museums, meals, and sightseeing?

But as has been said so wisely before, the adventure isn’t fun until it’s over. I soon saw a sign to a hotel and found it was adequate and at the right price. As I ran back I imagined what sort of scene I would find and decided there would either be a pack of unruly Bosnian youths harassing Bill and stealing our luggage, or the youths would be sitting in a semi-circle around Bill and laughing at one of his stories. But I was wrong on both accounts, and I found Bill calmly sitting on his suitcase like it was a park bench on a sunny afternoon. We gathered our things and hiked the last quarter mile to the hotel.

When everything was in the room and a couple of beers were ordered, I flung myself on the sheets and began to feel the built-up worry slide away to be replaced by the pleasure of a safe, warm bed. Bill stood in the middle of the room with his hands on his hips.

“You did good,” he said to me, and began to unpack his things.

Two mornings later, a search through my bags for a clean pair of pants caused me to unpack nearly everything I had, the wrinkled clothing and smashed stuff strewn across the room like a bad garage sale. At the sight of it, I realized was approaching my breaking point. Though we were on our way to Hvar, my baggage troubles were beginning to outweigh the island’s mystic appeal, and I was ready to take the next direct bus to Ljubljana. I told Bill this on the train ride from Sarajevo to Ploče, a town on the Croatian coast. The train departed early from Sarajevo and brought us descending along cliffs through the ghostly Bosnian mountains. Peaks appeared and disappeared in the fog and clouds, while green, stream-fed valleys held little Bosnian villages with smoke coming out of every chimney. The train passed through 102 tunnels before arriving at the city of Mostar and coasting onto the Croatian flats.

When we reach the final stop, I wrestled my bags out of the train, and Bill searched for information on ferries. He came back looking a little miffed.

“There are no boats to Hvar today,” he told me. “Or tomorrow. Maybe we can take another train to Split and get a ferry from there.”

“Bill, I think I’m going to find a bus and go north.”

“Let’s go down to the port and check it out,” he replied, and began rolling his suitcase away.

“Bill…” I said, but he didn’t stop. I thought about walking away, but instead gathered everything in my arms and trailed after him. After a ten minute waddle I turned a corner to see Bill talking with an official next to the loading plank of a large ferry.

“The boat leaves in five minutes,” he said as I reached him.

“Where’s it going?”

“Don’t know, but let’s go.”

“Bill…”

“We have to get a ticket at the office over there.” He pointed at a building a few hundred yards away. “I’ll guard the stuff, you run and buy them.”

“I don’t have any Croatian money,” I said, looking for any excuse to give up. Bill opened his wallet, which held six different kinds of currency, and handed me twenty English pounds.

“Go run and get it, I’ll wait here.”

“Bill…” I started to say more, but his look made me hustle towards the ticket office. I arrived out of breath and sweating and the lady behind the counter wouldn’t accept the foreign bill. She said I had to change it at a bank across town, and the bank was closed. I didn’t put up much of a fight and returned to the ferry at a slower pace. When I arrived, I shrugged my shoulders and handed Bill the twenty pounds. Instead of taking it, Bill picked up his jacket bag and walked onto the boat.

“COME ON,” he yelled as he wheeled his suitcase up the plank.

“BILL I DON’T WANT TO,” I yelled back, my frustration boiling over. Bill didn’t reply or look back. Two confused Croatian boat workers stood on the platform and waited for my decision. I looked at the sky and the clouds and then the twenty pounds still in my hand. A rising curse threatened to burst out of my mouth, but I took a deep breath and it disappeared. Then I picked up my bags and stepped on board.

Worth the trouble

Two days later I wandered around Hvar on a sun-bleached morning. The castle perched atop the hill looked down on this idyllic town: red clay roofs over white stone buildings, auto-less, cobblestoned streets and pleasure-cruising boats dotted the blue Mediterranean sea. Hvar still boasted perfect weather in September, but the main flock of tourists had gone back to their lives, and those of us still left on the island traded smiles at our luck. As I caught a delicious waft of baking fish from a restaurant along the waterfront, I found myself wondering where I would be if I hadn’t gotten on that ferry.

This is it,” he said to me as we clinked our glasses together “This is what all the tourists spend their time and money trying to find. All over the world…

When I’d met Bill on board, he handed me a crisp American two-dollar bill as a gift and thanked me for coming with him on this turbulent journey. On the top deck we watched ourselves chug towards the dry island hills in the distance, and the beauty made my anger completely slide away. The ferry took us to a small village named Tripanj, and there Bill befriended a bank guard who drove us to the other side of the island. Next we took a short boat ride to Korčula, and the following morning we found a ferry to beautiful Hvar. Once again it was my job to find a place to stay, and after I secured a pair of rooms, I found Bill drinking a fruit juice on the terrace of a seaside hotel bar. I sat down and waved down the waiter to bring a beer. It was 11 AM.

“This is it,” he said to me as we clinked our glasses together “This is what all the tourists spend their time and money trying to find. All over the world…” He looked wistfully out over the bay, an old man who has seen so many places in his life, and at this moment his eyes were resting on the place he loved the most. “This is it, right here. It doesn’t get any better than this.”

I could only agree.

Read more inspirational travel stories from normal people who have made travel a top priority and check out resources to help you do the same:

- From Corporate Tool to Nomadic Idealist

- Escape the Rat Race

- From Italy to China: A Leap of Faith in the Mouth of the Dragon

- Stop and Smell the Daffodils

- Travel in India: A Healing Journey

- Confessions of a Lifestyle Traveler

- Getting Your Boots Dirty: How Volunteering in Africa Changed Me

- From Cubicle to Coffee Shop: How Living in Santiago, Chile Changed Me

- Why We Decided to Road Trip Across Europe in a Self-Built Campervan

- Travel Made me Who I Am Today

- How a Dog Walk Changed My Life Forever

- Why You Should Forgo the American Dream and Let Travel Transform Your Life

- Getting Outside The Box: One Family’s Journey to Full Time Travel

- Check out our RTW Traveler Profiles and fill one out yourself

- Want some help planning your get-away from a BootsnAll team member?

Photo credits: LpstkLibrarian, Jeremy Vandel, brian395, all others courtesy of the author and may not be used without permission.