As a long-time Couchsurfer, I felt that once management put the values of venture capital funders over the organic, self-organized traveler base, and reorganized with a top-down, “start-up” mentality, the fall was inevitable.

When I logged onto Couchsurfing a few months ago in San Francisco, California, and put my hosting status as “available,” I expected, within days, to be bombarded. After all, that was how it was four years ago, when there were only a fraction of the members on the site as today. 7 million members, and, me, hosting in one of the most popular travel destinations in the world? I braced myself.

What happened shocked me. Days passed. Then a week. Not a single request, Despite 179 positive references and 42 vouches, no one wanted to stay with me. I asked my long-time Couchsurfing friends in the city and found it was the same for them. Sparse requests, and those that came, poorly-written, often from empty profiles. For others, guests who never showed up, messages that were never responded to. The site had changed. People were still attending meetups, but focused more on partying than sharing culture. The San Francisco group page was filled with travelers posting their plans, meeting to go sightseeing, but unlike before, nearly no locals.

I knew the situation was bad, but this was unexpected. The heart of Couchsurfing – hosting and surfing – was disappearing, and in the very same city where the site has its headquarters.

Then a few weeks later, total disarray. The savior of Couchsurfing, CEO Tony Espinoza, announced he was leaving after just 18 months. News came out about high turnover at CSHQ, with several staff leaving, followed by reports that cash is dwindling. To me, the surprise was not what happened, but how fast it came.

An idea that could change the world

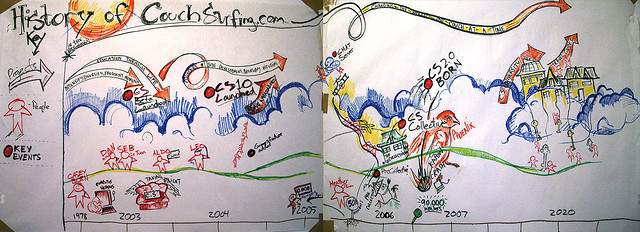

Couchsurfing didn’t invent hospitality exchange. That began in ancient times, when the first traveler knocked on a stranger’s door and was welcomed with open arms. What Couchsurfing did was utilize the power of a new tool – the internet – to enable and expand the natural human spirit of warmth and openness.

All of sudden, people with similar worldviews could connect over vast distances. Knocking on a stranger’s door turned into sending a couch request. Seeking friendly locals on the streets turned into travelers coming to weekly potlucks or cafe gatherings. The positivity was incredible – in the first few years as an active Couchsurfer, I never heard a single negative experience.

Couchsurfing was globalization done right – sharing culture and ideas with no or little financial transaction. Sure, access to the internet was a limitation in many countries, but that was only a temporary barrier that could be overcome.

Couchsurfing was globalization done right – sharing culture and ideas with no or little financial transaction.

Uniting over commonalities across cultures – that itself could change the world. That’s why I organized my first event in 2008, as a potluck in a San Francisco park – so that everyone could attend. That was why, then, I accepted every single request, regardless of profile, gender, or age. Because it was the right thing to do, the ethos of true globalism.

We built Couchsurfing, not management, who in those days did little more than provide a basic, buggy, but functional website. We who believed in the idea – the Couchsurfing spirit of sharing and openness – set up local groups, potlucks, events, and told our friends about this new, radical, and powerful social network. It wasn’t perfect; Couchsurfing had its turf battles, conflicts, and, unfortunately, an elitism exhibited by long-time members, but despite that, it was revolutionizing travel. The sky seemed the limit.

Warning signs

After my yearlong trip around the world – I used Couchsurfing extensively, as a host and surfer in Spain, Germany, Hungary, Turkey, Malaysia, Thailand, and Japan. It truly made my trip what it was, and I donated $50 to the site becoming a verified member, and I promised to donate more once I had a steady income.

[social]

Five months later, I was working for a non-profit in San Francisco, and, soon thereafter, Couchsurfing announced that it was opening a “basecamp” in the Bay Area, a place for volunteers to gather to help develop the site. The local community buzzed – this was a city had some of the brightest people in both technology and non-profit management. There was so much potential to work and build a stronger, better Couchsurfing that could, finally, meet its true potential.

They almost never came to San Francisco events, rarely had the community over, and gave little inkling of what was happening inside.

That hope quickly faded, as basecamp became a metaphor for the disconnect between management and members. Tucked away in a house in posh Berkeley, basecamp showed little interest in either the local community, or San Francisco’s vast knowledge network. Techie friends of mine tried to contact basecamp, eager to help fix some glaring holes in code or database structure, but were rebuffed. Basecamp members turned out to be Casey Fenton’s (Couchsurfing founder) inner clique, and they were unaccountable, and often invisible. They almost never came to San Francisco events, rarely had the community over, and gave little inkling of what was happening inside. Even more shocking – they were getting free rent, a generous per-diem, and even had an in-house chef with a generous budget. My donation was going to fund their vacations in comfortable California digs.

This lack of transparency, sadly, continues to this day. I never donated to Couchsurfing again, and I know few others who did.

The coup – Stealing Couchsurfing from its members

Despite the limited improvements to the site, members around the world kept organizing events, hosting surfers, and building the community. Then, out of nowhere, everything changed.

Couchsurfing announced they had failed to receive non-profit charity status and were going to reorganize as a B Corporation. In fact, they already had $7.6 million in funding from venture capitalists, and without any consultation with members, a new CEO, Tony Espinoza, had been hired.

It was a coup. The site we as members had built, the network we had organized, was suddenly under the control of a CEO who had never before used Couchsurfing, and investors who were interested more in the site’s monetary potential than its power to open minds and break barriers between cultures.

Millions of new members created empty profiles, while thousands of older ones stopped logging in at all. The site no longer represented what it once did.

Immediately, with money flowing in, member input became irrelevant. The wiki was removed, group pages were transformed, statistics about the site became “private information,” and the Ambassador program was revamped. The site transformed from a network of like-minded travelers to a start-up focused solely on growth. Millions of new members created empty profiles, while thousands of older ones stopped logging in at all. The site no longer represented what it once did.

Couchsurfing was now a “service” and experimented charging customers. The problem was that we, the members, were what management was trying to sell – the connections, networks, and communities we had built. They couldn’t profit off of our work, all around the world, because money was never a motivation. In 1 ½ years, Couchsurfing failed to monetize the site, leading to Espinoza’s resignation and the uncertainty the site finds itself in today.

The future of a nine-year old “start-up”

That Couchsurfing was having problems was no secret. My article on Couchsurfing’s downfall last May struck a cord – getting nearly 7,000 Facebook likes and hundreds of comments. Couchsurfing responded as a corporation would – with boilerplate PR talking points, copied and pasted to forums all around the web. One staffer, however, sent me a personal message, expressing surprise at my opinions and wondering if we would talk more about my concerns. Was this Couchsurfing finally listening? Was there hope?

It was, like basecamp four years ago, a facade. We met at a cafe, and for nearly 45 minutes, I was subject to being talked at about all the great things going on at CSHQ, why my article was wrong, and how all the Couchsurfers she knew (later I saw her profile only had 14 references, almost all from fellow staffers) were happy about the changes. It wasn’t a meeting to understand the frustrations and anger of members, but to convince me that HQ was right, and that we should trust in their opaque vision.

It wasn’t a meeting to understand the frustrations and anger of members, but to convince me that HQ was right, and that we should trust in their opaque vision.

I knew that anything I said wouldn’t be taken seriously. Couchsurfing didn’t have to go private. Members, like me, would have been willing to donate to the site if they could show, with full transparency, how money was being spent, and allow for greater participation in development. Instead, they rebuffed our attempts to help, ignored our concerns, and kept spending money in secret. So we never donated, and Couchsurfing was forced to seek unrestricted growth, and, eventually, private money.

Couchsurfing made a deal with the devil – venture capital money – and lost its base. It’s a lesson to any social network that aims to connect people in meaningful ways.

Empower your members, don’t disparage them. Be transparent and collaborative. As my experience in non-profit social activism has shown me, people want to be part of something big, to have ownership. Couchsurfing was built on that collaboration, and once that was taken away, everything we had built came crumbling down.

As any civil engineer knows, a building needs its foundation to stand strong. Likewise Couchsurfing needed its foundation – members – to survive. Let this be a lesson to all social networks built on trust and compassion.

To read more from and about author Nithin Coca, check out his author bio.

To learn more about Couchsurfing, check out the following articles:

- What Couchsurfing Meant to Me

- The End of a Dream: Couchsurfing’s Fall

- Re-Realizing the Dream: How to “Fix” Couchsurfing

- 10 Ways to Use Couchsurfing

- Couchsurfing: Tips for a Smooth Experience

Photo credits: phauly, eeliuth, lamoix, MasterMarte,