It was a combination of the tears on their faces and the high, warbling wail that ran chills down my back. It’s a bit odd, from our cultural standpoint, to just turn up at the funeral of some guy you’ve never met. Nicholas assured us it was fine, expected even, and that the more people turned out, the more honored were the dead man and his family. Nonetheless, it felt awkward to pass beneath the balcony with black veiled woman weeping and be escorted to our seats by a son-in-law of the deceased.

We drank the obligatory tea, cloyingly sweet, and munched on a plate of finger food that our hostess provided: some delicious cake, two sorts of psuedo-rice krispie treats and the rice flour and palm sugar snacks rolled in sesame seeds that I can’t quite stop thinking of as sweet cat turds.

The boys quickly made friends with a tribe of local kids while Nicholas brought us up to speed on Torajan funerals and this particular family.

The Funeral

We sip our tea, Nicholas pushes more of the cookies down our throats, people arrive bearing gifts, like water buffalo and pigs. We brought a carton of cigarettes, as we were told is “traditional” for travelers. Ezra is sorely disappointed as he had plotted, all of the day before, on how to “arrange a pig.”

Our boys are swept off with the local boys to supervise the buffalo and appraise their fitness for the occasion. They swoop in periodically to check for food. Lunch is served. Miraculously, the boys remember to roll their rice balls and pop them in their mouths with only their right hands. Elisha whispers about the meat looking a lot like the slabs we’ve seen laying out by the side of the road on tin roofs drying in the sun.

He asks Nicholas, “So… when they dry that meat in the sun, don’t the bugs get in it?”

Nicholas looks puzzled for a moment, and then answers in that quintessential adult tone of duh! “Well, yes!”

We tuck into our meat and rinse our fingers in the plastic bowl provided.

The Buffalo

He tells us that tomorrow, as the ceremony continues, they’ll sacrifice 30 buffalo. Today, they’ll sacrifice one, to help Grandpa’s spirit get to Puya, the region in southern Toraja that is “paradise” according to the Aluk Todolo, the old traditions.

And there she is: the buffalo, black as night, standing placidly next to a bamboo stake in the ground. She has that look about her, as water buffalo do, that makes us incline a bit and wait, sure she’s about to remember to say something profound. She says nothing. No last words.

Two things surprise me about her death:

- How quickly and deeply the butcher cuts with one, lightning quick, stroke of his razor sharp knife.

- How long it takes her to die.

Her eyes widen with the first slash, as if she really didn’t see it coming. Her throat erupts in a wide, arcing spray of wine red blood. She staggers, blood spurts again, coming in repeated gushes with every beat of her heart. She falls. She gets up. She strains at the rope tied to her ankle. She stumbles again. The butcher reaches in beneath her deadly horns and makes another quick swipe across her jugular. Blood gushes anew as she swoons like a drunkard, no doubt lightheaded from her exsanguination. She is laying on the ground now, sides heaving. She loses her bladder and thrashes her leg.

The women of the family have started drumming, with long bamboo poles inside a wooden trough filled with rice. This symbolizes the wealth of the family, Nicholas tells us. Young men are hoisting Grandfather’s casket house onto their shoulders, women are unrolling yards of blood red fabric, they are laughing and queueing up for their procession. The buffalo is not yet dead. In her final moment, she suffers alone. The last sounds she hears is laughter.

Elisha has blanched white: “I hope we don’t have to finish lunch, Mama,” he whispers to me. I share his sentiment.

The Party

“They didn’t consider the 7 P’s,” Elisha giggled at my shoulder. Indeed they did not. (Proper Prior Planning Prevents Piss Poor Performance!)

A wild cheer went up from the young men who had managed victory in setting the old man in his seat of honor. Having been a young man once, I can imagine that he didn’t mind so much. It was a festive scene, in the midst of which a buffalo cooled beneath a cloud of flies, weeping from her neck into a sea of her own blood, excrement dripping from the other end, children standing around, poking at her with sticks and fingers.

If I go the whole rest of my life without seeing another water buffalo sacrificed to be a spiritual conduit to the next world, that will be okay with me.

Burial in Tana Toraja

Skulls and femurs, ulna, and rib bones are stacked in piles everywhere. Many of the coffins have disintegrated, but their inhabitants have not. Hollow eyes stare out of holes in the rock where descendants have tucked the nameless faces to watch the world go by. Nicholas insists that we pose with a pile of skulls while he takes our picture, like any good guide would.

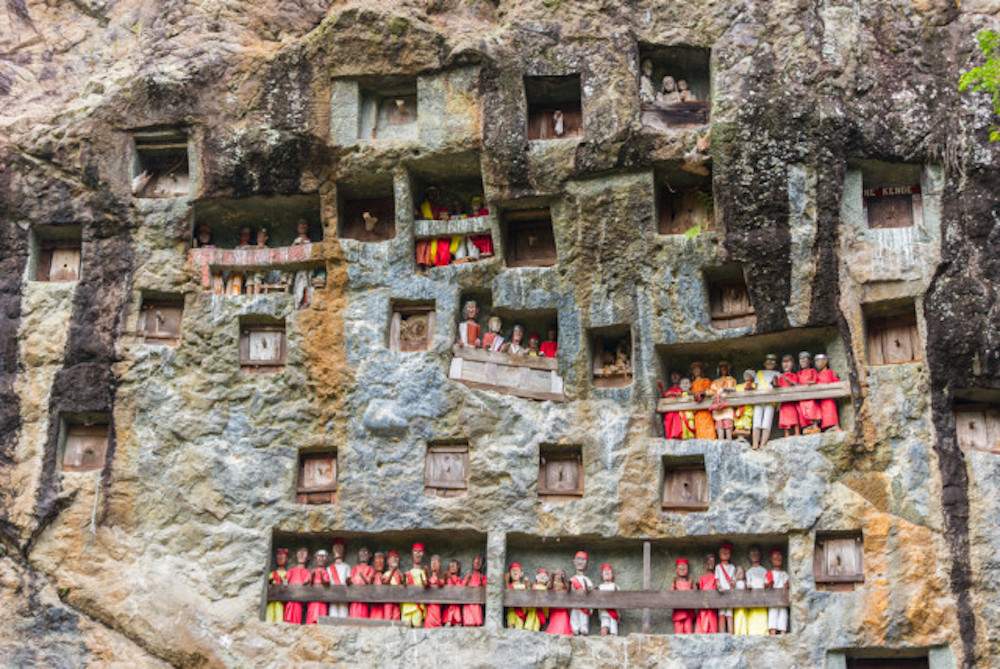

The graves here are carved high into the cliff face, and Nicholas explains that each grave is a large room and many bodies are placed in each one. Each wooden door indicates a family grave. Etched into the rock in between the mausoleum-like rooms are “balconies,” for lack of a better description. On these, the tau-tau are lined up.

Lifelike statues of the deceased, carved from Jack Fruit Wood, “Because this wood is very hard and is naturally the color of human people,” Nicholas explains.

It’s the color of Torajan people, at any rate. Their jointed arms are extended, flat eyes staring out of wooden features, a testimony to the generations of living, breathing, loving, hating, hard-working, hard-fighting people who have worn paths in the groove of this valley with the soles of their feet for thousands of years.

“The tau-tau are carved for the important families, the king people. They tell the story of the ruling families. They are important for preserving the history. Especially long ago, when we had no education, no writing, in Tana Toraja. The tau-tau told the story of the generations.”

I quietly wonder who they were. I stare into the worn eyes of their tau-tau and wish they could answer the questions I have. Their statues stand their endless watch, and I wonder what they make of our pale faces, strange clothes, and language. In that moment, the world seems a miraculous time machine to me, with hidden portals where worlds touch, threads of history almost intersect, and the tau-tau almost come to life and tell their story.

The baby grave tree was scary to me before I saw it. All I could think of was the other horrible tree that we saw in Cambodia this past summer. The one under which I was brought to my knees in gasping, mama sadness for the horrors perpetrated there. This was an altogether different sort of tree.

When their people die, they keep them in the house for a long time, allowing time to grieve, time to let go, time for life and death to fade together gently. Death isn’t the sharp cutting of a cord and immediate detachment that quick burial is. I kind of like that.

They craft tau-tau in the image of their loved ones, preserving a piece of them for future generations, as well as telling the stories through faces and eyes. They are amazing likenesses, some of them, and the very best of familial art.

They’v transformed death into something living, with their infant burials, a really lovely connection made between animal and vegetable, short lived, and long growing.

Death isn’t something to be separated from life. It’s merely the next step that we all take, and in this place the ghosts seem to hold hands with the living.

Have you ever attended a family event in another country where the cultural differences were as dramatic as the story above? Share your story below.