Anger Against America

Tehran, Iran

|

|

Demonstrators protest the U.S., but they also are quick to offer their hospitality to Kelly, an American, a guest in Iran. |

![]()

It is 4 am when I awake. I don’t know if it is due to the pack of wild dogs outside of window (well, at least they sounded wild), my mattress that has the consistency of concrete or the fact that it is my first full day in Tehran and I have an anti-American demonstration to attend.

It is the first Friday since the U.S.-led attacks on neighboring Afghanistan have begun, and the Iranian government is calling on the people to rally at Tehran University for weekly prayers, to be followed by a street protest. When I checked in the evening before at the Mashhad Hotel the manager warned me of the manifestation, which the government has been promoting all week during the nightly news. For the past three weeks I have seen the predictable “Down with the U.S.A.” painted on buildings throughout the country, but to see thousands of people chanting it in the streets, well, that is too good to pass up.

By 6:30 I am roaming the streets of Tehran, which are eerily quiet, this being a Friday morning, the Islamic day of worship. Just a few doors down from my hotel people are huddling around a small opening, and judging from the smells that virtually dance up and down the sidewalk, I guess they are buying bread. Women stand to the left, while men to the right, but within each line there is no sense of order. Finally I make my way to the window, where I am handed a fresh-from-the-oven flatbread measuring at least two feet long and six inches across, for mere pennies. As the protest is to start only mid-morning I decide to keep with the day’s theme of anti-Americanism, and so I head to the U.S. Den of Espionage, a.k.a. the former U.S. Embassy. With my loaf of bread in one hand and my Lonely Planet guidebook in the other, I go to the spot where 52 Americans were taken hostage back in November 1979.

Very few citizens of the Great Satan make it to Iran, but those who do await a surprisingly warm welcome. While their intense hatred for Uncle Sam goes unmasked, Iranians are quick to point out that they have no problems with the American people.

Upon hearing that I hail from the homeland of the enemy, people shake my hands, tell me about their relatives who have made it to America, pay for my bus tickets, and invite me for tea and even into their homes. And they all express sorrow and outrage about the devastating terrorism attacks on America. Never have I felt more welcomed and loved during my trip around the world than I have in the Islamic Republic. That is why it is even more shocking to see the anti-American slogans painted on the brick walls that surround what was once the embassy.

I know what to expect when I turn onto Taleqani Street, but seeing it takes my breath away. There they are, mural after mural, demonizing my country. The colors are vibrant and the artwork, in some cases, is quite good. Of course there is the ubiquitous “Down with the U.S.A,” but added to that are “When the U.S. praises us, we shall mourn,” and other sayings such as “United States of America After Ghods Occupier Regime (Israel) is the Most Hated State Before Our Nation” and “We Will Make America Face a Severe Defeat.” Twenty-two years after the hostage crisis the embassy is now an Iranian military installation, and I can make out armed soldiers patrolling from watchtowers. Now matter how tempting it may be, photos are forbidden due to the military nature of the compound, and according to my Lonely Planet photo-snapping tourists risk having their film torn out by the guards.

|

|

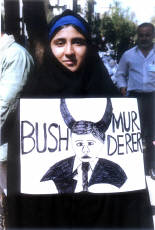

An Afghani woman holds up a protest sign of U.S. President George W. Bush. |

![]()

Up and down the avenue I stroll, running my hands along a Statue of Liberty, whose face now takes the form of a skull; a gun with the Stars and Stripes painted inside; the face of that radical revolutionary, the Ayatollah Khomeini; and an Iranian jet being blown to bits by an American bomb, killing over 250 people in 1998. In front of the main gate the embassy’s insignia can still be made out, and my fingertips gently trace out the words “Embassy of the United States of America,” long hacked out by irate Iranians, but the letters and an eagle are still clear to the eye.

With the streets still calm and the guards turned away, I stealthily pull out my camera and start shooting away. My family and friends know about the hostage crisis, but I want to be able to show them what decorates what once was our embassy. After about 10 shots I tuck my camera away, only to spy a guard peering down at me. With a brusque movement of his arm and twitch of his head, he angrily motions for me to leave. As I turn down the sidewalk I hear him calling out and my pulse quickens. He calls became louder, and while I doubt he will race down from the watchtower and come after me, my first instinct is to lift up my long coat and run like hell. But instead I force myself to continue walking in a calm and steady manner, without looking back at him. Once turning the corner I do make a mad dash for it. Anyways, I have to hurry up. The anti-American demonstration is going to start shortly, and I don’t want to be late.

As I make my way across town to Tehran University, minibuses with horns honking and young males hanging out of windows and waving Iranian flags weave their way past me. Looks like I am heading in the right direction, I think to myself, but in actuality I find out later that they are on their way to that afternoon’s soccer match with Iran playing Iraq. At the approach of the university security forces block off roads, and a few men and women straggle up the street.

Seeing that the entrances are segregated by sex, I follow a few chador-clad women, only to be turned away at the gate. As it turns out, being a foreign tourist I have to access the university through a special entrance. Round and round the campus I turn, hopelessly lost as I attempt to enter the grounds. Finally I approach a guard to whom I ask with a pointed finger, “Am-er-ee-ka?” In halted English he responds, “Down with,” and I figure that I am in the right place.

Though locals are already starting to flow in, I am instructed to wait until 10 am. While sitting on the sidewalk waiting to be let in, I spy a group of young adults who I figure can tell me what is going to happen and when. It turns out they are photography students who speak a smattering of English. Just then a television crew from France 3 pulls up, and so I chat with them a bit as well. Their Iranian translator informs me that I will not be allowed in with a camera and that I will have to wait for the street protest after prayers if I want to take photos. The university students concur, saying that you must have authorization in order to go in with a camera.

At 10:15 the France 3 team, as well as the students, all armed with the proper paperwork, venture in, and so I figure I might as well give it a try, expecting, however, to be turned away. Much to my amazement and delight not only am I let in, but I am also granted a press pass as well!