I was part of a group half way through a three-week trek exploring California, Arizona and Nevada. We’d arrived in the astonishingly beautiful Yosemite National Park and were given a choice of activities to do the following day.

The option which caused the biggest stir was the chance to hike to the top of Half Dome, a huge piece of granite with an elevation of more than 2,500 metres, the top of which can only be reached on foot.

Everyone in the group looked at each other, wondering whether they should go for it. I shrugged my shoulders and said: “I’ll do it. Sounds like a laugh.” But it wasn’t funny and no one was laughing.

Only two others decided to embark on the climb and together we listened to a briefing given by our guide. Because of the distance which had to be covered, we had to get up at four in the morning. A good night’s sleep was essential in order to ensure my energy levels would be at maximum for the next day. But it didn’t quite work out. The problem was that the group were a sociable lot and that evening we ended up having a bit of a party by the campfire. Suddenly it was two o’clock in the morning.

I grabbed two hours of much needed shut-eye and woke at four on the dot. Perfect timing, but not perfect physical state. The other two accompanying me on the walk emerged bleary-eyed from their respective tents and together, with our guide, we stumbled our way towards Half Dome.

Initially, with my head feeling as if a kettle drum drummer was enthusiastically banging away inside my skull, putting one foot in front of the other was proving to be a big ask. But before long the fresh air of this spectacular park cleared away the grogginess, and together we marched off along the trail with a spring in our step, though admittedly my spring could have done with a bit of work on it.

After about an hour, the positive march had deteriorated into more of an embarrassing stagger. My lack of preparation was already showing me up and I took no pleasure in periodically holding up my group to catch my breath, under the guise of tying my ‘extremely loose and troublesome’ laces.

The majority of the ascent involved walking. Or trying to. As we made our way higher up Half Dome, oxygen levels noticeably diminished – for me this resulted in conversations where six breaths were needed between each word, and by the end I could only cope with listening.

As we neared the top, people on their way down, on witnessing my pathetic wheezing and buckling legs, would offer uplifting words of encouragement.

“You can do it!” they shouted, with a clenched fist.

“Yes, but maybe not today,” I wanted to reply.

The last 30 minutes were the toughest – not necessarily because I was completely drained of energy, or that my lungs had probably shriveled to the size of raisins – but because the walk was becoming ever steeper and the path narrower. My ability to concentrate was fading almost as quickly as my will to live.

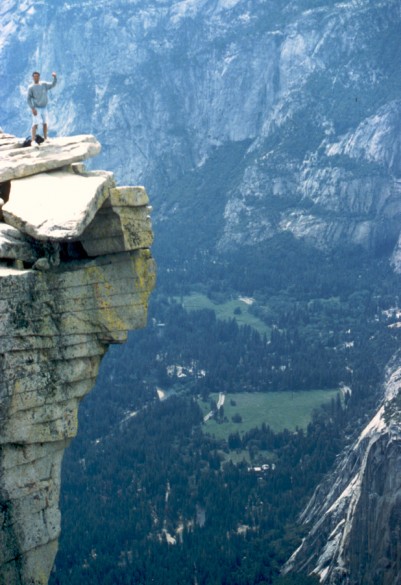

Eventually we could see the top. I felt a rush of adrenalin and knew I’d be all right. We took a brief rest before taking on the final ascent. This involved pulling yourself up a metal railing fixed into the rock. It was 120 metres in length and at an angle of about 70 degrees.

My guide surveyed the build-up of clouds in the sky and nonchalantly commented that if a storm broke out while we were at the top, we’d have to beat a pretty hasty retreat.

Has anyone in your tour groups ever been struck by lightning?” I asked, more out of a need to know we’d all be fine rather than a wish to hear how some poor exhausted climber had ended up a fireball. My guide’s answer, however, failed to reassure me.

“Let’s just focus on the positive,” he said as he looked skyward. “What’s meant to be is meant to be.”

Before I embarked on the final climb to the top, I closed my eyes and said a quick prayer, hoping that having ten million volts of electricity pass through my body while vacationing in a Californian national park wasn’t meant to be.

I began to haul myself up the metal railing to the top. My legs were already like jelly and now my arms were taking a pounding.

On reaching the top, my aches and pains, as well as worries about the weather, fell away into the valley below as I stood in awe of the scene before me. Indeed, the stunning view would’ve taken my breath away, if I’d still had it.