On the Bolivian Trail of “Che”

Vallegrande, Bolivia

Battling a dreadful dose of the “runs” and a horrendous bus ride, I made it safely to Vallegrande, Bolivia without enduring any human systemic disaster. Leaving Santa Cruz last night, the Flota Bolivar bus bumped and jerked its way along the old Cochabamaba road at a snail’s pace. With each abrupt movement my guts wrenched and twisted violently in knots. Apart from a brief panic stop at Samaipata, miraculously I managed to keep my “cheeks” securely clenched. If the cramps and the cold sweats was not enough to deny me any comfort, being squashed between five people on a backseat built for four, ensured that any chance sleeping would also be a miracle.

Jolting to a sudden halt, the bus pulled up to the curb two blocks from the main plaza. I tugged at my luggage and bolted for the nearest hotel. For once I was in no condition to compare prices or negotiate. I needed a toilet… urgently, a pit …anything, just somewhere I could relieve myself of this agonizing curse. And, I desperately needed a bed.

In true Latin American tradition I had become accustomed to a “siesta” and after waking from some much needed respite and an alleviating spell on “el baño”, I strolled hungrily up the cobbled street toward the town centre.

Encircled in barbed wire, the humble little square in various stages of decay contained numerous pictures and graffiti dedicated to the Argentinian revolutionary, Ernesto “Che” Guevara.

Beside me, an old man quietly watching the stream of people moving busily about the market from one of its dilapidated benches, looks up seemingly bewildered by my fascination with this otherwise unremarkable landmark. “Buenas señor,” he said…but most likely thinking “crazy tourist”.

Who could have believed that 30 years after his execution, Guevara would be immortalized in the very same place where his battered and lifeless corpse was proudly displayed as the prized scalp of the Bolivian army? …And that of the CIA.

Abruptly, a cold, sweaty sensation and violent rumbling below alerted me to race back to the safety of my hotel with its toilet in close proximity. It seems my stomach was still far too tender to savour any of the local delicacies… the markets were just going to have to wait.

|

|

Airstrip Graveyard, Vallegrande |

The next morning I was gently woken by sunlight creeping through a fine gap between the blinds. It was 9:30 and it was the best I had felt in days and for once the cramping in my belly had not kept me awake. The Flagyl (antibiotic) was finally having its desired effect.

Walking away from the town’s centre, I headed downhill toward the little airstrip nestled peacefully at the base of gently sloping green hills of the Western Cordillera. Entering through the gate of the “Aeropuerto Capitan Vidal Villa Gomez”, I passed a group of young men too engaged in their game of soccer to notice me heading toward the inconspicuous mausoleum standing solitary in the distance.

Since Guevara’s disappearance in 1967 and his discovery in 1997, this secluded little airstrip with its neat white picket fence, hid the cadaver of one of history’s mystical revolutionary figures.

Clambering through the barbed wire fence I made my way round various trenches and old excavations toward the small, partially built structure. Entering under its terracotta roof, I approached a chipped, black wrought iron fence surrounding the gravesite, when a sudden cold chill crept along my spine. Only this time, it had nothing to do with my bowels.

|

|

A simple wooden cross marks the now empty grave |

With Guevara now reburied in Cuba, I peered into the vacant sepulchral pit where flowers in various stages of decay and melted candles lay at the base of a simple wooden cross commemorating where his remains once secretly lay. The cross bore the inscription “Para la Solaridad, la libertad y la Justicia” – For solidarity, freedom and justice – honouring the achievements of this idealistic warrior. Another small plaque dangling from its top read encouragingly, “Let us be like Che”.

I could not help but ponder over the life of this remarkable man and his achievements, the Cuban revolution, the Congo and ultimately his death here in this obscure little place, fighting for a cause so far from home. For decades his mysterious disappearance remained the talking topics of many conversations and led to many unsuccessful expeditions, some in the very region where he was later discovered.

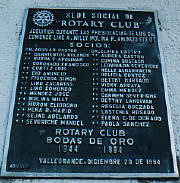

Leaving the unfinished mausoleum, I followed a well-trampled trail through the dry shabby grass up an embankment past an old cemetery. Seemingly lost, I found myself on a back road that seemed to wind back toward the centre of town. I stopped an old man walking a dog and asked him for directions to the Rotary club. “Ahi, mas adelante, señor,” he directed me, pointing with his cigarette in the direction to where the wanted street should materialize. “Gracias,” I replied and marched on.

At last, I found the ghostly complex locked behind an intimidating barbed wire fence. Nervously looking round to see if anyone was watching, I scrambled under the wire causing my alpaca jumper to snag on a rusty barb. I worked furiously to unhook myself but could not without sustaining a large tear over the shoulder.

|

|

The abandoned Rotary Club |

Slowly edging my way towards three mounds visible in the distance, I passed the moss-riddled tiles of the club’s derelict swimming pool. A creepy sensation enveloped as I approached the sites where Guevara’s fallen comrades had been buried in mass graves. Slightly disturbed by the discovery, I found it difficult to read the names on the clay plaques honouring the fallen men and women.

I shivered from the creepiness that enshrouded the area. Not even the warmth radiating from the midday sun high in the Andean sky could penetrate the iciness that I felt as I withdrew from the deserted complex.

The Village of La Higuera

Inside the colourful but dully lit market, food stalls and produce tables are cramped side by side. Each stall almost indistinguishable, including the smiling campesina with her white top hat and brightly coloured petticoat… selling the same fruit and vegetables or eggs at the same price and each beckoning simultaneously, “Compra me señor“… buy from me. To the rear more identical stalls all offering breakfasts of chicken stew, soup and coffee or a more traditional “maté de coca” (Coca tea).

Keeping in mind my delicate stomach, I opted for a breakfast of freshly processed juice – banana, orange and papaya. I had to turn a blind eye as the lady washed my glass with her hands in a grubby bucket and then dried it on her apron. I’m sure this was the cause behind my recent bout with Giardia.

Differentiated only by a modest chequered plastic tablecloth, I plonked myself down on one of the identical wooden tables, next to a man busily tucking into his chicken stew. Finishing my delectable pulp, I interrupted the man’s breakfast to ask where I could catch a transport to the village of Pucara, from where I intended to continue to La Higuera.

Following the man’s instructions two blocks up the narrow cobbled road running parallel to the market, I reached a corner where a number of people stood or sat around waiting on the curb beside a row of identical white Toyota station wagons equally divided in the middle by a rusty Dodge pick up truck.

After asking various people waiting which was the taxi to Pucara, I decided to approach one of the station wagons lined alongside the footpath. Finding the right driver he advised me that he needed seven people to fill the car before he would leave.

My biggest test in frustration was yet to evolve in my attempt to gather the necessary numbers to make the trip. Meandering through the small group gathered on each of the corners asking people their destination it seemed like I was the only one desperately wanting to travel. When it seemed I had gathered the necessary numbers, others would vanish. Seeking assurances from the others to wait until my return, I pleaded with the last man over a cup of coffee finally convincing him to follow me immediately to the little white wagon. Two hours later we finally did have the numbers to go.

Being the obvious tourist, I was politely guided to the front. Adjusting the seat belt and feeling satisfied that my little exercise was not in vain, when the driver advised me that I was to share my seat with a young girl. Trying to position her thin frame so as to not impinge on my comfort, the shy girl introduced herself as Mar y Sol. She was travelling with her auntie on their way back to Pucura from the markets.

Bending down to adjust my bag under my feet, I nearly poked myself with one of the multicoloured wires poking their frayed copper ends through a large round hole in the dashboard. Even more puzzling, I discovered the odometer and fuel gauge glaring directly at me above the opening. Where was the steering wheel? Looking back toward the driver I noticed that the steering column was now rising out from the glove box. Like many of Vallegrandes’ Toyotas, this wagon was a cheap used Japanese model that had been imported from Chile and then undergone a makeshift backyard conversion.

The conversion was not the only thing that was rough. The 45 kilometres to Pucura took three long hours along a pot holed and corrugated road. On arrival to Pucura I found the town to be uninhabited, ghostly, with dilapidated buildings shading a little rectangular plaza. My fellow passengers soon got out and also disappeared. There did not appear to be any form of transport apart from our recently arrived taxi.

Having no other option I negotiated the fare for the remaining 15 kilometres up to the village of La Higuera. The hour long trip proved to be even more cumbersome and at times hazardous, requiring me on numerous occasions to get out to move rocks out of the way or to direct Manuel round tricky obstacles. Along the way Manuel pointed out important landmarks including “Vado del Yeso” where Guevara and his guerrillas were ambushed and finally captured.

|

|

La Higuera Memorial |

As the white wagon made the final curve into La Higuera, a giant effigy of Che Guevara confronted me. Who could have imagined 30 years ago in the very place where he was hunted down and finally executed there would be monuments to his failed efforts to start a revolution? Annually, on the 8th of October, admirers from all corners of the globe make the pilgrimage here to La Higuera to pay him homage. To the right of the giant bust, a little shady plaza in need of pruning contained a smaller bust of Guevara, barely visible in the shadows of the overgrown shrubs.

Today this mountain village stands mostly as it would have three decades before, the little school, now a medical clinic has been recently renovated and painted a little. “Una Pepsi, señor?” came a voice from behind me. An old woman with the most wrinkled face that I have ever seen was offering me one of her warm bottles of Pepsi cola. With a gentle smile I kindly declined her offer. She slowly made her way toward another low thatched building with its wall thickly covered by hundreds of inscriptions and dedications written by the numerous visitors who have come to pay their respects to this fallen hero who perished here.

Such was the impact left behind on the quiet and dreamy streets of these two little Bolivian towns. It seems that every citizen has a different story to tell of the events of that chilly October night, which catapulted their insignificant tiny mountain villages to the vanguard of the world’s media.

As the sun began its slow descent over the green mountains it was time for meBolivian Trail of “Che” to commence the uncomfortable crawl back to Vallegrande.