Out of the Mist

Treasures of the Nuu-chah-nulth Chiefs

Captain Cook first encountered them in 1778 on Vancouver Island’s remote, windswept west coast when his ship, wrapped in thick fog, rang its bells. “Nootka, nootka” – cries came over the water through the mist as the aboriginal people in their war canoes warned the ship it was about to crash on the rocks. The word stuck, and the inhabitants of this distant coast were called the Nootka people for almost 200 years until, in 1981, they officially changed their name to Nuu-chah-nulth, meaning “all along the mountains”.

“Our history runs to the place before time”, said Stan Smith, a member of the Ehattensaht band of the Nuu-chah-nulth people. And that is what this exhibit at the Royal British Columbia Museum is all about. It showcases the arts and culture of the 19 tribes whose territory stretches across 300 km of Vancouver Island’s west coast and 5-7000 years back in time. Though only 12,000 strong, the First Nations people want to maintain their own identity, and they feel the exhibit is a way to teach others about their rich history.

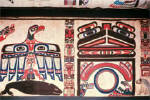

“When we sing our songs, when we show our masks and headdresses, we invoke the presence of our ancestors. We are collapsing time,” says a sign at the exhibit. That sense of the past is powerfully present in these 241 artifacts and 75 images that express a deep reverence for the sea, land and creatures.

The Museum, working with the First Nation’s People, planned the exhibit to reflect four areas of their lives – the people and the land, the cultural and ceremonial properties of the chiefs, the presence of their ancestors, and the contemporary people and their culture.

The exhibit, collected from over 20 museums in Canada, the United States and South Africa, gives a sense of the powerful belief these people have of the relationship between the natural world and the spiritual world. The subdued lighting, recorded drumbeats and chants of the people bring that feeling home.

The tribes perform special ceremonies that bring these the world of the spirit and the natural world together. Four wolves’ headdresses tell of a particularly powerful spiritual preparation in a sacred place – the Wolf Society Ceremony, Tluukaana. Elders take young people to a sacred spot for eight days to teach them about their heritage and their family, their songs and values and instill respect for their elders. When they return home, the children act as if possessed by supernatural spirits. Ceremonies are held to drive away the spirits, followed by feasting.

HuupuKwanum is a name meaning a chief’s storage box in which he keeps all inherited rights – names, dances, masks and privileges. Examples of these are shown at the exhibit in such objects as family curtains and crests that depict in visual images the inherited rights of the chief’s family, much as details in a family Bible were once kept in our culture. The Frank Family Curtain, a spectacular decorated 24-foot (7.5 metre) cotton ceremonial piece, was purchased from the Andy Warhol collection.

An impressive collection of masks, rattles and wrapped twine baskets further emphasizes the heritage of the people and their belief that “everything is one”. Masks tell stories about the experiences of ancestors with both the animal and spiritual world. Especially of note is the wooden mask given to Captain Cook on his encounter with the group in 1778. This mask travelled on his ship to Hawaii and was given to the governor of the Cape in South Africa by the crew after his death. It truly invokes a sense of that far distant time.

On display are woven spruce root and cedar bark hats, called whaler’s hats, which were collected by European visitors in the late 18th century. These hats denoted the high social status of the wearers. Fewer than 20 early hats exist in museums today. Two in this display date from 1794. Model canoes emphasize the importance of that mode of transportation for fishing, trade, economy and spiritual life.

Headdresses were used in ceremonies. Some were made of red cedar boards sewn together with bundles of sticks and feathers attached to the top. An unusual headdress in the exhibit is made of cedar slats painted like feathers with a feather fan that opens and closes. Another elaborate one opens out on hinges, revealing a human face with a bird’s beak.

Rattles, many carved in the shape of birds, are used to accompany songs and chants. Traditionally they represent great power and are sacred objects. On one initiation rattle a man sits on the back of a bird while a wolf bites his head and a serpent rises out of the wolf’s back. Another displays the carved head of a serpent integrated into the body of a whale.

Creative tradition continues to be a living part of the modern community. Salmon, birds, and other natural objects figure prominently in the contemporary work on display. Changer masks, where a dancer spins and rapidly changes masks to convey various facial expressions, are still used in ceremonies today.

Baskets of different shapes and sizes, decorated with colorful designs, play a modern role in the cultural pride of the Nuu-chah-nulth. This is not art to be put on display as we think of art. But rather as Ki-ke-in (Ron Hamilton) says, “I think of what I do, and what my ancestors did, as making cultural things, full of meaning and usefulness and power.”

This contemporary society with a long and proud history is sensitively portrayed in this moving and mystical exhibit. It brings a strong appreciation of this ancient culture to the viewer and an understanding of their belief that all things in the physical world relate to the spiritual. The Nuu-chah-nulth say, “Chuu” for goodbye, but the images and spiritual aura of this exhibit will stay with the viewer for many years to come.

Essential Information

The Royal British Columbia Museum is located at 675 Belleville in Victoria, BC, Canada on Vancouver Island. Tel. toll free 1-800-447-7977. Open 9am-5pm daily.

The exhibit runs until June 1, 2000 at the RBCM and will move to the Denver Museum of Natural History in Denver, Colorado, USA, from October, 2000 to January, 2001. The RBCM hosts a permanent, related exhibit, First People’s Gallery.

©2000 by Barbara Ballard. Reproduction of this work in whole or in part, including images, and reproduction in electronic media, without documented permission from the author is prohibited. Images courtesy Royal BC Museum.

——–