I remember hearing my Dad say that it was his express goal to put my brother and I in the social situation of being the only caucasians within 500 miles and letting us get comfortable with that. Indeed, there were long stretches of our childhood where we were the outsiders and we learned to bridge the gaps, find our feet in strange and uncomfortable situations, communicating with fingers and smiles where words failed us. Having had that kind of childhood, the world seems a smaller and kinder place, to me, than it does to some others. It also makes it infinitely bigger and more marvelous.

I’m going to make a bold assertion. One that, perhaps, people will disagree with and argue with me over. One that may get me called names in the end, but I’m going to make it all the same:

I don’t believe that you can fully come to grips with the richness and diversity of the world, or your place in it, without traveling at least a little.

- There is absolutely no substitute for standing in the middle of a foreign city, far from all you know, and having the realization that you are profoundly out of place.

- There is nothing for building compassion like being discriminated against yourself, based on the color of your skin, your religious persuasion, or the stamp on your passport.

- There is nothing that develops solidarity with foreigners in your own country quite like being one in theirs.

- There is nothing that more quickly builds appreciation for the gift of your life and freedom in a democratic country quite like realizing you’re one blog post away from imprisonment and deportation in many parts of the world.

Travel introduces you to the world, in all of it’s sticky, dusty, multi-faceted, politically complicated, religiously diverse, bigoted, beautiful, glory. But more importantly, the world will introduce you to yourself.

Experiencing is different than reading about it

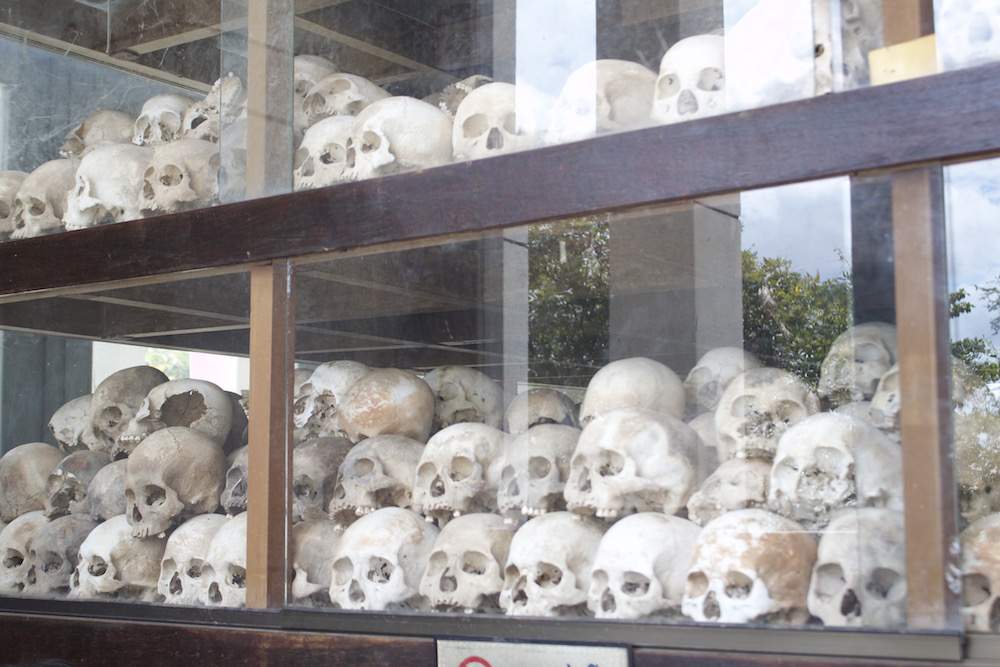

He looked at me with tears in his eyes, “Pol Pot was a very bad man, Mama. This is just like Germany. Just like Hitler. Why did this happen again?”

I kept it together, at least on the surface, until my oldest son, white as a sheet walked up with eyes like blank saucers and whispered in a hoarse voice, “I just stepped over a jaw bone. There were teeth…” He kept walking, as if motion itself would be enough to carry him away from the horror.

Then, there was the tree. The tree that is seared into my heart and mind forever. The tree that the soldiers used to beat the babies to death, swinging them by their feet while the music blared loud enough to cover the screams of their mothers, forced to watch as their children, their hearts, their lives, their futures, were destroyed in the most vicious way possible. Their own, subsequent deaths must have been welcome for many of them.

Experience is a powerful thing

I’m showing them pictures of Canada, trying to explain “snow” as an abstract concept and explaining that it’s a country somewhere north of the USA, which is the big country north of Mexico. They can almost grasp it. One girl traces my white arm with her brown finger while we talk. I’m enormous to them. My kids are a comedy in size difference. It takes a few minutes before I figure out what’s not right: There are no boys. No big boys, at any rate.

The girls giggle and are reticent to reply. Finally the answer emerges from behind shy grins and twinkly eyes. “They are working.”

By the time they’re in the fourth grade they are big enough to work in the fields, so they are pulled out of school to work like the men. The average educational level for an indigenous child in Guatemala is 3rd grade. They don’t learn Spanish until they enter school. These factors, among others, are what conspire to keep them from participating politically and socially in a way that would empower them.

I watch the wheels turning in my daughter’s head. She was 14 at the time. We’re at this school because she’s raised money to buy books for the classrooms, and we were invited to the ceremony celebrating the literacy program Co-Ed Guatemala was putting into place. Education is everything.

I’m a slow learner, and fiercely committed to teaching my kids to work, so I don’t hire house help, but on the fourth day, I finally opened my eyes. I offered her a pot of tea and cut up a watermelon for the two children who were with her. They scampered off into the garden to play on the vine with my tribe, and she and I did our best, in her second language and my third, to begin to become friends. She’s the mother of six, married to an alcoholic mess of a man who drinks his way through the little money he manages to make. She struggles to keep her kids in school, but they need shoes to go to school, and shoes are expensive.

“Can you weave,” I finally ask.

She looks at me as if I’m simple. Of course she can weave, she was practically born at a back-strap loom, she’s Mayan, after all.

“Could I hire you to teach me?” I ask.

She smiles and laughs deeply, looks out over the garden at our kids swinging on the vine and answers me, “Si, yo puedo. Regressamos manana.”

True to her word, she appears the following day and we head up the big hill to a local market where she haggles hard to get me supplied properly; I could never have managed it without her.

And so my lessons began. I did learn to weave, in spite of my inability to sit properly in the loom or make my big fingers do what her small ones did deftly. One afternoon, her daughter Maria, age 13, was standing over me watching my every move, waiting for me to make a snag.

I looked up at her, “Maria, can you weave better than me?” I asked.

She covered her mouth with her hand and giggled, shaking her head back and forth refusing to answer.

“It’s okay you can tell me the truth. You CAN weave better than me, can’t you?!” I winked.

She collapsed into giggles and confirmed my suspicions. Yes. She could. In fact, Fatima, her baby sister could weave better than me. I rewarded her with a glass of Coke. She adjusted the little bamboo stick that kept my progress straight, and I settled into what was henceforth known between Maria and I as my “preschool weaving class.”

We worked together, one long spring, to educate me, and empower her, in the process selling all of her weavings over Facebook, which was nothing short of magic in her technology-free world. There is more that I do not know, than I can ever know.

They are cheering and clapping as the flames fill the belly of the stove and we’re explaining to them that these heat entire houses in our corner of the world. Just a few months ago we were on their turf, and their mothers, or women like them, were carefully enunciating Thai words for me, and remembering that I wanted my order “baby spice” when I ordered papaya salad every week in the market. What goes around, comes around – we all have our lessons to teach.

The short list of what the world has taught me so far

- Humanity is big. I am very, very small.

- I am not the solution. Very often, I am the problem.

- I am not the problem. Very often, I could be the solution.

- Part of the problem, or part of the solution. Every day, it’s a choice.

- If there is conflict, the answer is usually that I need to get over myself in some capacity.

- If there is to be understanding, I must listen and be teachable.

- My culture is not the best culture.

- My culture is not the worst culture.

- My culture is only one of many, and of equal value.

- I am powerless sometimes, and that’s a fact.

- I am powerful all of the time, even if only within my own soul.

- Artificial humility and false pride are two sides of the same coin, neither one helps the world.

- Self-deprecation renders you useless, lay your talents on the table.

- Reach out, be willing, live “open.”

- The little bit I can do may not matter to “the world” but it might mean “the world” to one person, and that is enough.

- When I am weakest, I find strength I didn’t know I had.

- Children are the universal language of love and laughter.

- Old people are the best teachers.

- Living from my passions is the only way to change the world.

What is the world (and your travels) teaching you? Tweet us @bootsnall #doyouindie

- Searching for Summer: How Travel Saved a Teenager from Self-Destruction

- Immerse Yourself in a Culture While Learning

- Educational Travel: How to Get Permission and Justify the Experience to Your School

- Long Term Travel as Education

- Lessons from Around the World: 11 Skills to Learn on Your RTW Trip

Photo credits: Muslianshah Masrie , all other photos by Jennifer Sutherland-Miller, may not be reused without permission