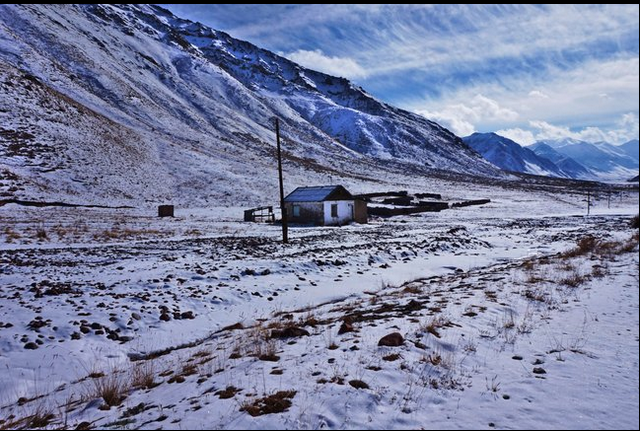

Central Asian countries aren’t exactly known for being well-developed, especially in the Pamirs region, which tends to have harsh weather conditions and hardly any roads. The borders close in the winter due to the roads getting buried under meters-thick blankets of snow. The locals in the Pamirs region are habitually bracing themselves for the hard months ahead.

I was making my way south through this boundless land in November, which is pretty much the last minute before everything freezes.

Just 11 days before, at the very end of October, I had crossed the border between Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan merely a couple of hours before it closed until May. It was then that I realized that time waits for no one – the next close call might leave me in front of a barred gate over some other line in the snow. So I hurried across the country and soon found myself at a crossroads with one road leading to Dushanbe, the capital of Tajikistan, and the other ascending to the Pamir mountains, among the world’s highest.

It has been my goal to visit the Pamirs.

I even went to Bishkek, the capital of Kyrgyzstan, in order to acquire a permit to enter Tajikistan’s Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Region (GBAO). So here I found myself, permit accounted for, trying to hitch a vehicle going south. But there were none, all of them opting for the route to Dushanbe.

“The trucks never go in that direction,” an employee at the crossroads weigh station informs me.

Keeping an eye on trucks is literally what he does here, so I reckon he knows what he’s talking about. The passage promises to be difficult, but I keep my hopes up, waving a thumb at the rare landrover passing by and even at a random shepherd jogging by on his horse. 1.5 hours later I score a lucky lift in the car of one of the border guards heading to work. Traveling south by an old, cracked, arrow-straight road, he tells me we could observe Lenin Peak from where we are, but unfortunately, it’s obscured by the clouds.

The Wasteland

We soon arrive at the border post and parted ways. Passing the customs is a breeze. The guards are friendly and polite, they soon open the gates and tell me that beyond lies the neutral strip of land of about 18 km until the next border post that belongs to Tajikistan.

“Beware of wolves,” says the guard, closing the gates after me,

“Beware of wolves,” says the guard, closing the gates after me, “they can be vicious beasts, sometimes coming very close to our fences.” 18 km is not a reasonable walking distance in the afternoon with a 30 kg backpack on the shoulders, so I keep doing what generally I do in these cases – looking for a ride to hitch.

It takes the rest of the day.

I’m waiting on the side of the road, occasionally doing squats and pushups on the pavement to warm myself up as it gets colder and colder. The only cars passing are tightly-packed cargo taxis full of locals who are visibly surprised to see a foreign man with a weird hat and a humongous backpack all alone in the middle of nowhere. There are just two cargo taxis today and both are heading in the other direction, so no lift for me.

4 hours have passed since I started my roadside vigil, and the sunlight is now touching the snow-covered mountains. Still, the cold is becoming a major concern.

All of my warm clothes just aren’t enough to ward off the icy caresses of the wind. I have the camping gear and the tent with me, which will probably be enough to keep me alive during the night. Wolves don’t concern me much; I travel with a huge Nepalese kukri – it boosts my confidence if nothing else. I’m sure I can make it through the night in one piece.

Nevertheless, I have no idea just how cold it gets here and the wind is gaining strength, so I really would prefer not to sleep out in the open. I start looking for alternatives, one of which is squatting in the only building around, an abandoned old house on the side of the road. I go to investigate and it turns out to be locked. The snow around it is littered with canine footprints. That’s not a good sign.

I decide to try my luck at the border post, maybe they will allow me to wait for a car in a warmer place for a couple of hours. Making my way back, I ask for permission to enter and am allowed to wait in the passport control booth. Still no cars for hours, though. As I’m about to leave and set up the tent before it’s completely dark, an old man comes over and invites me to stay in a warm room for the night. That’s more than had hoped for, so I gladly accept.

The night at the border post

My host turns out to be the veterinarian inspector of the post and a bit of a spiritual leader for the tiny isolated community of Kyrgyz soldiers. They are all quite friendly and welcoming. We share some food in a metal wagon with a hot burning stove, exchanging stories and strong drinks. In no time I make the acquaintance of almost everyone there. They come to chat with me one by one. It’s not every day they receive visitors there, I wasn’t supposed to be inside the post territory at all. But here I am, treated as a guest, and in this part of the world, the traditions of hospitality are still strong.

After my host performs the last namaz of the day, I can finally get some rest on the floor of his modest but warm cabin.

Thus I cozily spend that night on the Kyrgyz border post, instead of being frozen, devoured, and whatnot in the unwelcoming wilderness.

A truck comes the next day and my new friends hitch that ride for me, convincing the driver to take me into a cabin with 4 people inside already. This is a rare occasion – the truck is carrying goods specifically to the Pamirs for Murghab and Khorog markets. So I arrive at the Tajik side located on the Kyzyl-Art pass with the altitude of ~4300 m, where the guards check my GBAO permit and lazily inquire whether I’m carrying any drugs or weapons. Somehow I forget to mention the kukri and they let me through without a problem.

I bum around this post for a few hours as the Tajik guards show their own hospitality and treat me to berry tea with cookies. Finally, I get my last ride of the day to the town of Murghab which disappoints me immensely, even with my humble expectations. The town doesn’t have a single ATM, and the only bank is closed for the weekend. I never bothered to acquire the Tajik somoni before and that’s left me with 4$ and 1080 Kyrgyz som (~16$).

To add insult to injury, local “hotels” don’t have any showers, and I desperately need one.

Internet connection is not a thing here and the electricity comes from a diesel generator for just a few hours in the evening. Rusty metal stoves burn inside the carpeted rooms, providing a little much-needed heat.

I still manage to get by with the money I have, even scoring a ride to the only open bathhouse of the town, also diesel-powered. Trees simply don’t grow at this altitude and the combustible fuel delivered from afar is the only option here.

In this unlikely place, in the same homestay I stopped for the night, I meet a Portuguese traveler, João, who is exploring the world with his wife and little son in a van. The van’s heating system broke and they ended up in the same place that I did. Although we go our separate ways in Murghab, our paths will meet again in the next town on the Pamir Highway, Khorog. We later met by pure chance in a restaurant and then again in the homestay I used. Occasions like this make the immense Pamirs look tiny and cramped.

All in all, it took me about two days to cross the Kyrgyz-Tajik border

…including a one-night stay in the hospitable Kyrgyz checkpoint and then spending my last dime to pay for a homestay room on the following night.

That forgotten mountain land may seem immense, but in reality, it’s where I learned the meaning of the expression “Small World” via the communities and friends I came into contact with.